…I…follow along behind a small group of conservation officers heading to the lawn outside. Their leather hiking boots squeak as they walk. “So she looks in her rearview mirror,” one is saying, and there’s a bear in the back seat earing popcorn.” When wildlife officers gather at a conference, the shop talk is outstanding. Last night I stepped onto the elevator as a man was saying, “Ever tase an elk?”

Mary Roach is up to her old tricks. A science writer now publishing her seventh book, Roach has written for many publications, including National Geographic, Wired, NY Times Magazine, and many more. She begins with a notion, then goes exploring. Roach tells Goodreads, in a book-recommendation piece, that she came across a potential story about cattle breeders staging deaths to commit insurance fraud. She even had a grand theft avocado story lined up, but the local Smokeys would not let her come along, which was a requisite. She shifted to wildlife.

I paid a visit to a woman at the National Wildlife Service forensics lab who had authored a paper on how to detect counterfeit “medicinal” tiger penises. – from the GR piece

Wait! What? (there is link to the study in EXTRA STUFF, of course) But again it was nogo accompanying the officers into the field. Really? Her presence would blow a National Wildlife Service raid on a market selling junk johnsons? It is pretty easy to come up with a descriptive for such unwarranted reticence. (Rhymes with sickish.) In any case, in her investigative travels, Mary came across a weird 1906 book about the prosecution and execution of animals and realized she had her hook. What if animals were the perpetrators of crimes instead of people? She breaks the book down into “criminal” categories, homicide, B&E, man-slaughter, larceny, even jaywalking, and off we go.

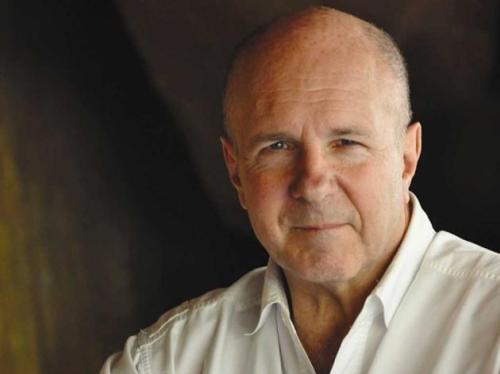

Mary Roach – image from Lapham’s Quarterly

First, and foremost, I need to let you know straight away that you will be laughing out loud at least every few pages. This is not an experience I have with any other writer, and yet have had it consistently with Mary Roach, across the several books of hers that I have read. Ditto here. Well, fine, your sense of humor may not be like mine, but Mary has the key to my funny-bone.

Her intro offers a stunning representation of just how stupid people have been when attempting to enforce laws on animals over the course of history. Python-worthy material, totally side-splitting, and jaw-dropping. Really, they actually did that? Yes, gentle reader, they totally did.

On June 26, 1659, a representative from five towns in a province in northern Italy initiated legal proceedings against caterpillars. The local specimens, went the complaint, were trespassing and pilfering from people’s gardens and orchards. A summons was issued and five copies made and nailed to trees in forests adjacent to each town. The caterpillars were ordered to appear in court…Of course no caterpillars appeared at the appointed time, but the case went forward anyway.

It goes on. Would have been tough making a charge stick anyway. They would have just blamed each other. It was that caterpillar, not me. I was nowhere near that orchard. And even if they were jailed they would have just flown out anyway. The law may be a ass, far too often, but sometimes it truly boggles the mind.

As usual, Mary interviews experts in all the areas she investigates. She begins her contemporary explorations with a gathering of Canadian Conservation officers (in the USA) getting Wildlife Human Attack Response Training or WHART. They don’t, but you go right on ahead and call it what it is, CSI-Wildlife – DUUUUUM-DA-DUM! Mary brings plenty of funny to her reporting, but a lot of it is simply laying out the facts and letting them make you laugh themselves. For example, the test manikins are named for brands of beer. Good one, eh? And there is that quote at the top of the review. You will also learn some real-world intel like the significance of a round versus a more oval drop of blood at a crime scene.

As usual with Mary, you will find yourself learning a whole bunch of information you never knew you wanted to know, like how to tell the difference between a bear and a cougar kill. (No, not that sort of cougar, the one with fur and claws, a mountain lion, Geez! and no, no, no, not that sort of bear, creatures of the Ursus genus, not those other large hairy beasts. Stop that right now!) She considers issues with elephants, leopards, cougars, bears, macaques, gulls, vultures and other birds, rats and mice, trees, and beans. Come again?

The lines here get a bit vague. It is not just animals that are the focus but some non-critter-based elements of nature as well. Sticking with critters for the moment, there are considerable challenges in managing the interface between people and animals. For instance, the vig that farm mice seem to extract from farmers regardless of what is done to get rid of them can turn peaceable crop-growers homicidal. Mary looks at the control methods that have been tried, and explores a promising, more laid-back approach.

Rats in the Vatican (which is an outstanding name for a band, just sayin’) present the challenge of managing the property while taking seriously the lead of Saint Francis of Assisi, an animal rights figure of long-standing, and a major inspiration for Pope, ya know, Francis. Mary talks to the guy in charge of this problem (I could not help but imagine Father Guido Sarducci, sorry), the Vatican Director of Gardens and Garbage, Rafael Torning. The considerable Vatican rat population has a taste for wires, and damages a lot of machinery. VG&G does what they can, trying to avoid using nasty chemicals. But even so, aren’t there ethical concerns? So, she talks with the house bioethicist, Father Carlo. Let’s just say that if you could count the number of angels on the head of a pin, Father Carlo could very nicely twist all of them into pretzels with his words.

A possible solution to half of the Vatican’s Gull-and-rats problem? – image from the Irish Sun

The Vatican has a considerable problem with herring gulls as well, thousands of ‘em. None of this Mary Poppins Feed the Birds nonsense. The feathered rabble that descend on Saint Peter’s seem more like the gathered horde in that Hitchcock movie. You will not come away from this book fond of gulls. I found her lapsed-Catholic’s tour of the Vatican to be worth many, many indulgences, rich as it was with fun details and ambience.

Chapters on elephants and leopards are particularly alarming.

…when a leopard stalks and kills more than three or four people, villagers consider it a demon. – [it, clearly, considers them takeout]

There was one historical case in which a single leopard killed over a hundred people. Mary travels with government and non-government people as they try to educate local populations in best practices for avoiding potential conflict. Not all leopard attacks are the same. You will learn the sorts. And not all attacking leopards are handled the same way. She looks at changes that have been at least partially implemented to try to reduce the carnage. (Indoor toilets, for example), and the challenges going forward in handling the problem, getting leopards to leave people alone.

Leopard – image from Wild Cats India

When it comes to elephants, Mary Roach knows her shit, literally. She reports on a Smithsonian project that measured daily defecation by an Indian elephant. A poop scooper will not do. Maybe a poop plow? 400 pounds, give or take, per diem. Elephants loom large as a danger, laying waste to crops, trampling fields and bulldozing buildings. People are sometimes accidentally trampled. Sometimes it is no accident, as when one elephant did a headstand on someone. A bull elephant in an elevated period of breeding excitement, called musth, is particularly aggressive and a mortal peril. She can also tell you about the effectiveness of small arms against big pachyderms. Keep your powder dry. Most bullets do little or no damage. Even a bit of armor-piercing ordnance intended for tanks needs a follow up to get the job done.

Indian elephant in musth – image from Wikipedia

Monkeys in India come in for a look. Macaques in particular, have made pests of themselves in urban areas, becoming aggressive thieves, to the point of violence, and even of extortion, as some will steal your phone, handing it back only when you pay the fee in food. Government officials struggle to come up with solutions, tough in a place where the monkey is a sacred animal. It is impossible to deliver directed doses of birth control without endangering other native wildlife, for example. Roach delivers a bleak portrait of official finger-pointing and inaction.

Street Monkeys in India – image from Outlook

While reporting on the damage done to area farms and people, and the impact of wildlife in places populated with humans, Roach does point out that a lot (all) of these conflicts result from people expanding into the native territory of dangerous or potentially pestiferous, animals.

I was surprised that there were parts of the book dedicated to non-creature natural perils. The material is interesting, but thematically it felt a bit off the central topic.

There is much surprise information (well, for me anyway) about “danger trees,” those fully grown trees that have come to the end of their lives, at least in terms of growing. They still serve as useful woodland citizens by providing places in which creatures can nest, wood in which bugs can live, biomaterials that will be absorbed back into the woods. This is all good, but there is still one problem. The rotting tops of these gentle souls can come crashing down on passers-by, unaware of the peril. The approach that is taken, by woodland managers makes one wonder whether it is better to yell “Timber” or “Fire in the Hole!”

Decay throughout this tree makes it too hazardous to fell with a saw. It was felled with one bundle of fireline explosives taped to the side of the tree – image and text from the US Forest Service

There is an element in this book that you should be aware of. The disposal of animals considered pests. This is of particular relevance in places where invasive species have arrived and laid waste to significant segments of the local fauna, and/or flora. Not all of these are the usual suspects, stowaway rats wiping out bird populations with their fondness for eggs, brown snakes, ditto and far too many others, often foolishly introduced by people attempting to counteract an earlier invasives problem. Some of the invaders are adorable and not on your likely list of things that MUST BE EXTERMINATED NOW. Mary looks at the techniques attempted (usually failed) and on the thought that goes into trying to make a creature’s passing as quick as possible. You might want to skip that chapter (14). Many of my daily companions are on that list and, although I did read it all, it was disquieting at times. Just lettin’ ya know. I hope this does not turn you off the book if you are otherwise interested.

She does focus on ways in which people can live in coexistence with nature. This includes a greater understanding of the deer-in-the-headlights syndrome, and a workable approach for reducing roadway carnage.

Deer in the headlights – image from Bryans Blog

I have issues with the titling of the book. The raised-patch addition to the hardcover jacket goes very nicely with the patches my wife and I picked up at many US National Parks. Mary might have called it Nature Gone Wild, but that was already taken. Naming it Fuzz, though, (maintaining the tradition of single-syllable Mary Roach book titles) does make it seem like it is about the police-type officials who are charged with coping when forces of nature interfere with people. Although there were indeed some badged officials in her stable of interviewees and guides through these fascinating worlds, she spoke as often with people who were researchers or administrators, and the stories were about the problems, not so much the law enforcers. Many may be related to parks here and there. Some were employed by wildlife services, but it just did not sit well with me. Her reporting is as much about a wider view of the issues as it is about the direct, Book-em, Danno “crimes” supposedly perpetrated on people by the furry or feathered set. So, I will not shy away from this. When it comes to actually describing what the book is about the title is decidedly fuzzy. There. I did it, and I am not sorry. Well, ok, maybe a little. Not that I can come up with anything better, just whining.

That done, it is clear that wherever Mary Roach shines her light there will be surprises, there will be new knowledge, and there will be smiles, lots and lots of smiles, covered with copious quantities of laughter. Follow along behind Mary as she opens some closed doors, peeks into some hidden corners, and pesters defenseless officials to find fascinating, wondrous real-world material. Even despite that one grim chapter, I found myself reacting as I always do to a Mary Roach book, laughing out loud, often, very, very often. There is a definite joy in trailing after Mary as she shines her very bright light into unseen corners and calls back “Hey guys, come see what I found!” If you have enjoyed her books before, this one should do quite nicely. There is nothing fuzzy about that at all.

Feeding animals, as we know, is the quickest path to conflict. The promise of food motivates normally human-shy animals to take a risk. The risk-taking is rewarded, and the behavior escalates. Shyness becomes fearlessness, and fearlessness becomes aggression. If you don’t hand over the food you are carrying, the monkey will grab it. If you try to hold onto it, or push the animal away…it may slap you. Or bite you. The Times of India put the number of monkey bites reported by Delhi hospitals in 2018 at 950. [When your teenager makes off with your car, just remember that it all began when they were small, and you made the mistake of offering them food]

Review posted – October 29, 2021

Publication date – September 21, 2021

I received this book from Barnes & Noble in return for cold, hard cash

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal and Twitter pages

Interviews

—– Mary Roach Discusses Craft & Humor in Science Writing With the Northwest Science Writers Association with Hannah Weinberger and Ashley Braun of Northwest Science Writers Association – video – 1:05:08 – Covers her entire career

—–Commonwealth Club – Mary Roach’s Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law – with Kara Platoni – audio – 1:04:44 – a lot of fascinating material in this one – more focused on this book

—–Bookpage – Mary Roach – Hot on the trail of nature’s outlaws by Alice Cary

—–Goodreads – Mary Roach’s Highly Unusual True Crime Recommendations

Other Mary Roach books we have enjoyed

—–2016 – Grunt: The Curious Science of Humans at War

—–2013 – Gulp

—–2010 – Packing for Mars

—–2006 – Spook

—–2004 – Stiff

Items of Interest

—–National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory – Distinguishing Real Vs Fake Tiger Penises – Where it all began for Mary re this book – You know you’re curious – yes, there are illustrations

—–The Guardian – Vultures who came to stay bring year of acid vomit and toxic feces to small town by Adam Gabbatt – Geez, talk about pests!

—–NY Times – Indians Feed the Monkeys, Which Bite the Hand by Gardiner Harris

Songs/Music

—–Mary Poppins – Feed the Birds – Julie Andrews

Scrabble Words – from the book, to weaponize against family and friends in the game

–—-frass – insect excreta – white powder that appears on trees (Not a birch! Please do not lean there.)

—–kerf – space left by a saw-blade cut in a tree (not necessarily by a man wearing a leather mask)

—–kronism – the eating of one’s offspring (named for Saturn. Did not work out well for him, though)

—–musth – a periodic condition in bull (male) elephants characterized by highly aggressive behavior and accompanied by a large rise in reproductive hormones. (from Wiki) (aka Friday night?)