While many short lengths of rope helped countless individuals through the centuries, rope also was a tool of human innovation writ large through collective action. Just as many small strands come together to form a rope, so, too, did many people gather to perform the biggest of tasks. The exemplar of this from the ancient world is the Egyptian pyramids. While we don’t know exactly how these human-built mountains were assembled, we can be sure that rope was an essential tool in their construction. In this way rope stands as both a tool and a symbol of humans working together to achieve the greatest things.

The concept of rope remains timeless; what changed over millennia was the application of the human mind toward making ever better rope and in devising ways to use it.

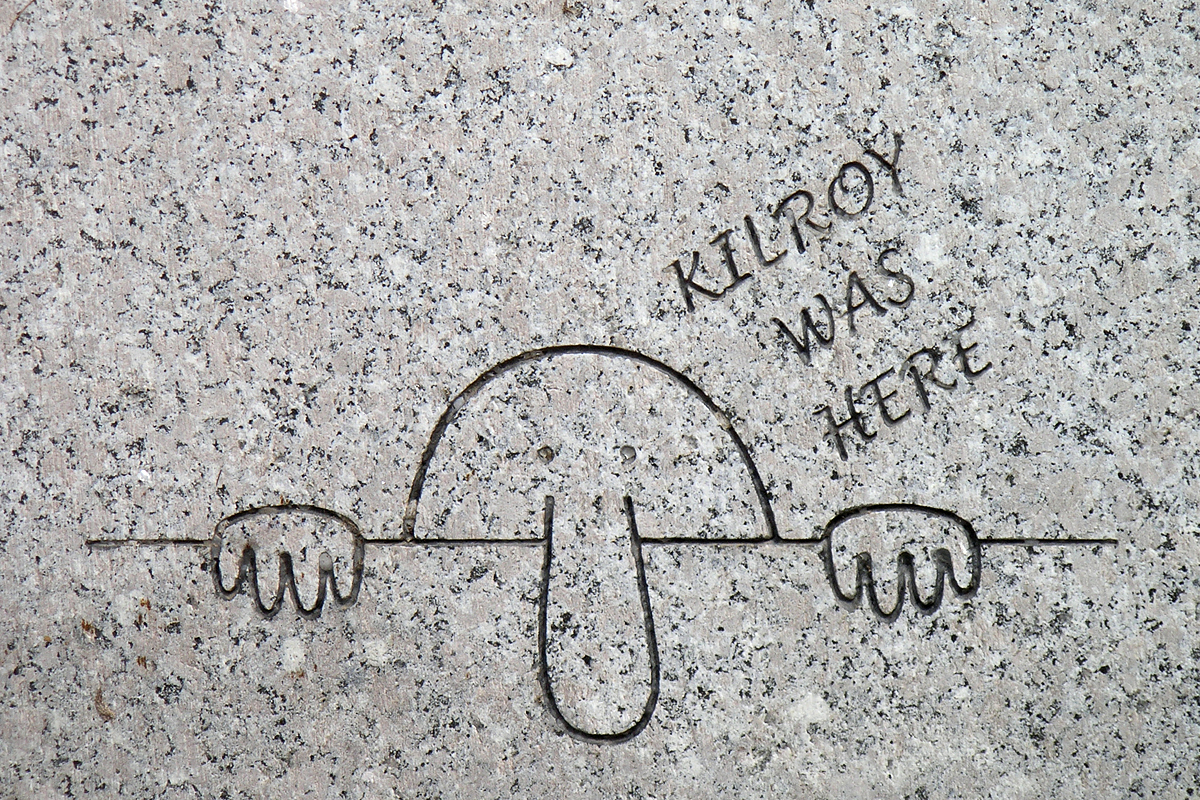

Neanderthals used rope 50,000 years ago. Did Homo Erectus, Habilis, Australopithecus, or any of the sundry other homo genus cousins get there first? Dunno. Maybe, but no thread of evidence for any rope-making before Neanderthal has been found. Still, it was a helluva long time ago, and ropy material tends not to survive forever, unlike stone tools, so…maybe. Makes rope rank with fire and stone tools, (although, rope was a form of tool-making, it probably came after stone tools) as basic elements of civilization. (Oh, and let’s not forget Duct Tape)

Tim Queeney – image from his site – shot by Molly Haley

The breadth of this book reminds me of the opening scene of

2001:A Space Odyssey, taking us at it does from the dawn of tool-using man (or pre-man) to the futuristic apex of a 21st century space station. Tim Queeney takes us on a past-to-future journey of similar timescale, albeit without the perplexing Star Child ending.

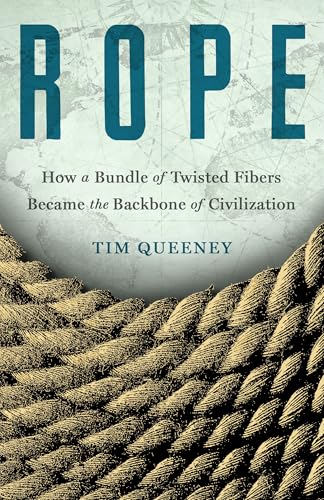

There are books that cover a seemingly narrow subject in vast depth. I have read several of this sort, stovepipe books I suppose one might call them. (Banana, A Perfect Red, The Age of Deer, Eels, Just My Type, or many others) It is usually the case that the information revealed therein broadens our appreciation for the subject matter at hand, generating a lot of reactions like, “I never knew that,” or “wait, what?” Rope could be considered a stovepipe book in that it is focused on a seemingly single thing. Yet, once one dives in, it soon becomes apparent that the subject matter is massively broad, touching on a vast array of human history and enterprise. It seems less a narrow stovepipe look than a Poppins-esque vista of the rooftops of London. For a book of such modest length, it offers a broad, deep, and surprising look at one of the seminal tools of human existence.

Image from Disney

For Tim Queeney, this book is an homage to his nautical father, the man who taught him everything he knows about sailing, making manifest the emotional and experiential ties that bind father to son. As one might imagine there is a vast amount here related to seamanship through the ages. And much wisdom to be had for aspiring sailors and fishermen. He notes knots in abundance. Sadly, in the AREs that I read, paper and Kindle, there were no illustrations of these or the other devices and tools that Queeney describes. I cannot say if this is also the case in the hardcover release. I added links to a couple of old seamanship books in EXTRA STUFF if you find yourself wanting some instruction on how to twist and tie (or untie) this or that obscure tangle of rope. And there are sundry images available on Queeney’s site, although not on knot tying, at least not that I found.

The Lifeline by Winslow Homer – from the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In a slightly related vein, it was fun to learn of the need for rope skills in the world of entertainment. Maneuvering sets on stage take a set of skills that any sailor would easily recognize, and that any stage pro would need to have mastered.

My personal experience with rope is minimal. I recall as a stripling hanging out with friends in the Morris Heights neighborhood in Da Bronx, a place that offered the presence of sundry empty lots. There was one in particular, a large one that featured a singularly tall tree. I have no idea which foolhardy child undertook the task, but someone had climbed up that tree and slung across a sturdy branch a rope that ended in an engorged knot about fifty feet below. (Well, of course, someone with a strong arm might have just tossed it up and over from the ground, but where’s the fun in imagining that?) The Bronx is a hilly place, so the improvised swing began on the uphill side and swung out over the downhill side. Losing one’s grip at top could result in a slight bruise and a dose of embarrassment. Letting slip on the downhill side, particularly if the drop was unintended, could result in weeks in a cast. I swung out on this very thick knot of rope a time or three, but, being of a risk-averse sort, considered that sufficient. My other related, rope-involved escapade occurred as a much older idiot. I will not repeat it here, but direct you to my review of Rivers of Power for the mortifying details. Otherwise, no further rope-related personal experiences of note pop to mind, so you are spared that.

Section of cable showing strands in the cables supporting the Brooklyn Bridge – image from Catskill Archive

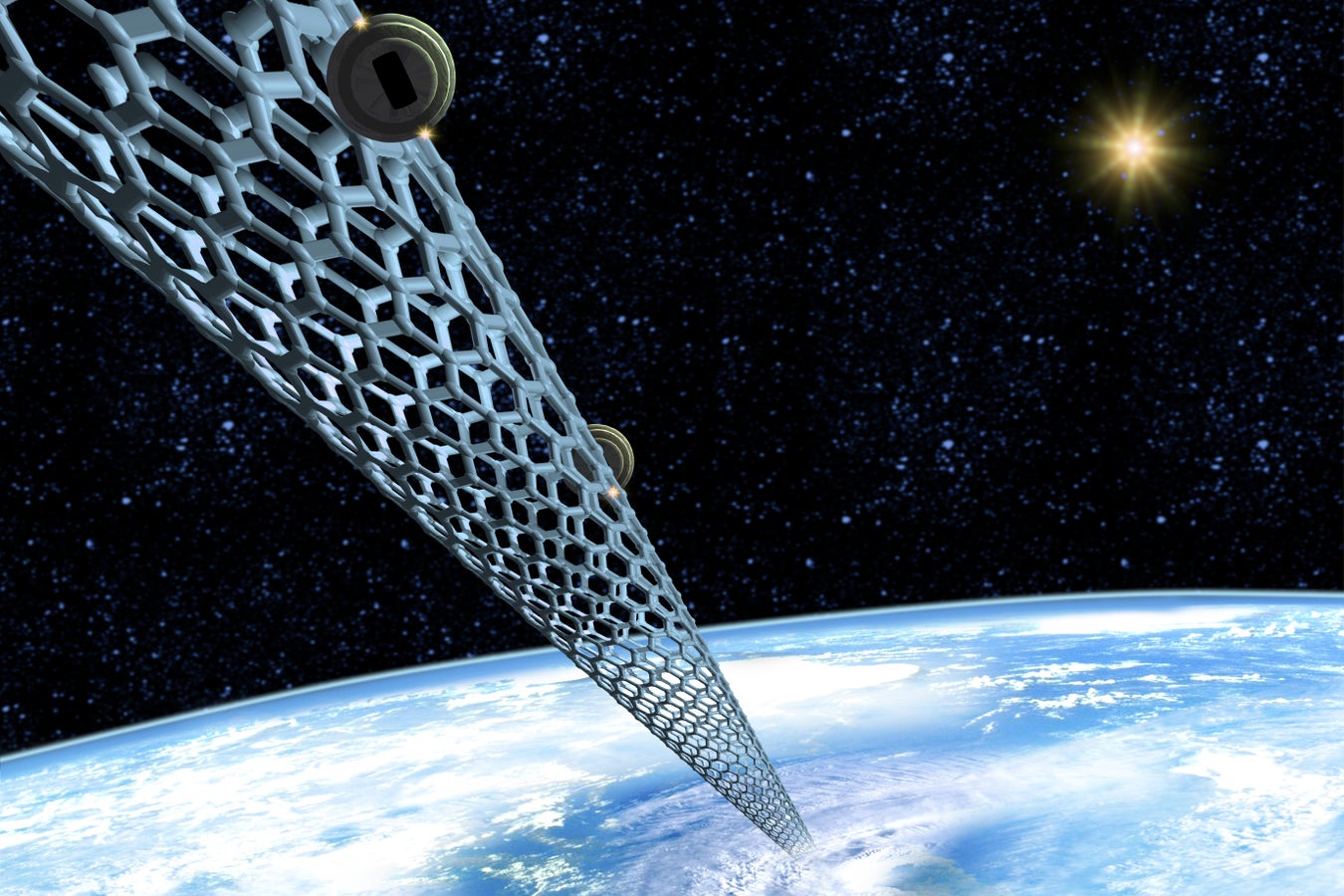

There is also a lot having to do with things quite far removed from the briny deep and the boards. Major world constructions of diverse sorts, pyramids, and ancient megaliths, for example. Surprisingly, in Inkan (Queeney’s spelling) traditions, rope, khipu, was used, through an intricate language of knots, to tell stories. One could say that these ropes in particular were used to create yarns. Some might, but not me. You will be surprised to learn who perfected the art of the lasso. And then there is some history on notions of knots in the realm of matrimony. As with so many things, one person’s tool is another person’s weapon. He racks his brain to report on rope as a tool of restraint, pain infliction, and termination. Subjects cover land transportation, the manufacture of rope, construction, communication (sub-Atlantic cables) rope tricks, climbing, space exploration and plenty more. He also provides considerable attention to materials that were used in the past and the materials that make up much of the rope-assigned tasks of our age, from the invention of rayon and nylon to the use of metal like steel, to the superstrength fibers of today, like Kevlar.

A drawing of how the steep ramp, poles and ropes could have helped the workers lift the huge blocks of stone used to construct the pyramids. – image from Kids News

Queeney has a very engaging style. Only rarely will you find it necessary to struggle past some technical jargon. His enthusiasm is infectious. No mask needed. He will throw a lariat around your attention and slowly pull you in.

A space elevator made of carbon nanotubes stretches from Earth to space in this artist’s illustration. – image from Scientific American – source: Victor Habbick Visions/Science Source

Whenever anyone proclaims “no strings attached,” you should know better. Rope makes it clear that there are, and for at least 50,000 years always have been, strings attached, and that without them, we might still be traversing waterways powered by oars and muscle, communicating face to face, and satisfying ourselves with building structures of exceedingly modest dimensions. The discovery and implementation of rope technology has allowed us, as in the Indian Rope Trick, to climb into places we had never known before. So does this remarkable book.

Review posted – 08/15/25

Publication date – 08/12/25

I received digital and paper AREs of Rope from St. Martin’s in return for a fair review. Thanks, folks, and thanks to NetGalley for facilitating. And, uh, I held up my end, so could you untie me, please?

This review is cross-posted on Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to Queeney’s personal, FB, Instagram, Twitter and Blue Sky pages

Profile – from his site

In addition to writing books, I was the longtime editor of and columnist for Ocean Navigator, a magazine for serious offshore sailors. At ON I also taught celestial, coastal and radar navigation as an instructor for the Ocean Navigator School of Seamanship, both in hotel meeting rooms ashore and on tall ships at sea. I love to sail, hike, get lost in museums and spend timeless hours drawing and painting. I’m a dad to three sons and a rescue dog. Am a NE Patriots and Arsenal fan and tend to reference a Stanley Kubrick film every two minutes or so. I’m also that annoying night sky watcher who is always pointing out the constellation Cassiopeia — because its forms a big W, which reminds me of my wonderful wife, Wendy.

I live in Maine and can hear the fog horns of three lighthouses when the fog rolls in.

Interviews

—–History Unplugged – Rope Equals Fire as Humanity’s Most Important Invention: It Allowed Hunting Mammoths and Building Pyramids – with Scott Rank – audio – 58:27

—–Rope Equals Fire as Humanity’s Most Important Invention: It Allowed Hunting Mammoths and Building Pyramids – text extract of the above podcast

—–Maine Calling – Rope by Jennifer Rooks, Jonathan P. Smith – audio – 50:36

Items of Interest from the author

—–The History Reader – Rope’s Role in Colonial America’s Tarring and Feathering

—–Queeney’s blog

—– Dragging a Ship Uphill? Gonna Need Some Rope – On Werner Herzog making Fitzcarraldo

—– Ben Franklin Gets Juiced With a Little Hemp

—–Rope Ends: Moving Massive Stone Blocks the Natural Way

Items of Interest

—– The Kedge Anchor, or, Young Sailor’s Assistant – an 1847 source of knowledge maritime, including instructions for tying dozens of sorts of knots

—–The Ashley Book of Knots – 1944 – thousands of knots, with illustrations

—–Earth-Logs – Earliest evidence for rope making: a sophisticated tool by Steve Drury

—–Arcanth – Making Rope – Medieval to Edwardian technique – video – 2:49 – this is amazing!

—–Wiki – the Indian Rope Trick