Before I started searching for life in the cosmos, I just assumed scientists knew how it started on Earth. We don’t.

…it is sobering to realize that for most of Earth’s history, humans would not have been able to survive on this planet. If we could rewind Earth’s history and start again, it seems unlikely that Earth would produce humans again. A planet with different starting conditions and paths of evolution has no obligation to support life similar to Earth’s, let alone curious humans.

The truth is out there.

Are we alone in the cosmos? The question should have an obvious answer: yes or no. But once you try to find life somewhere else, you realize it is not so straightforward.

At least until the age of permanent haze across the planet, we have always had the stars in our consciousness. Since the second century AD we have had stories about alien worlds. Since Galileo we have been able to see other worlds in the cosmos. A 1792 novel by Voltaire tells of an alien encounter. Concern about extraterrestrial locales has been a part of human consciousness ever since. The concern is certainly fed by the history of strange human invaders helping themselves to land distant from their home soil.

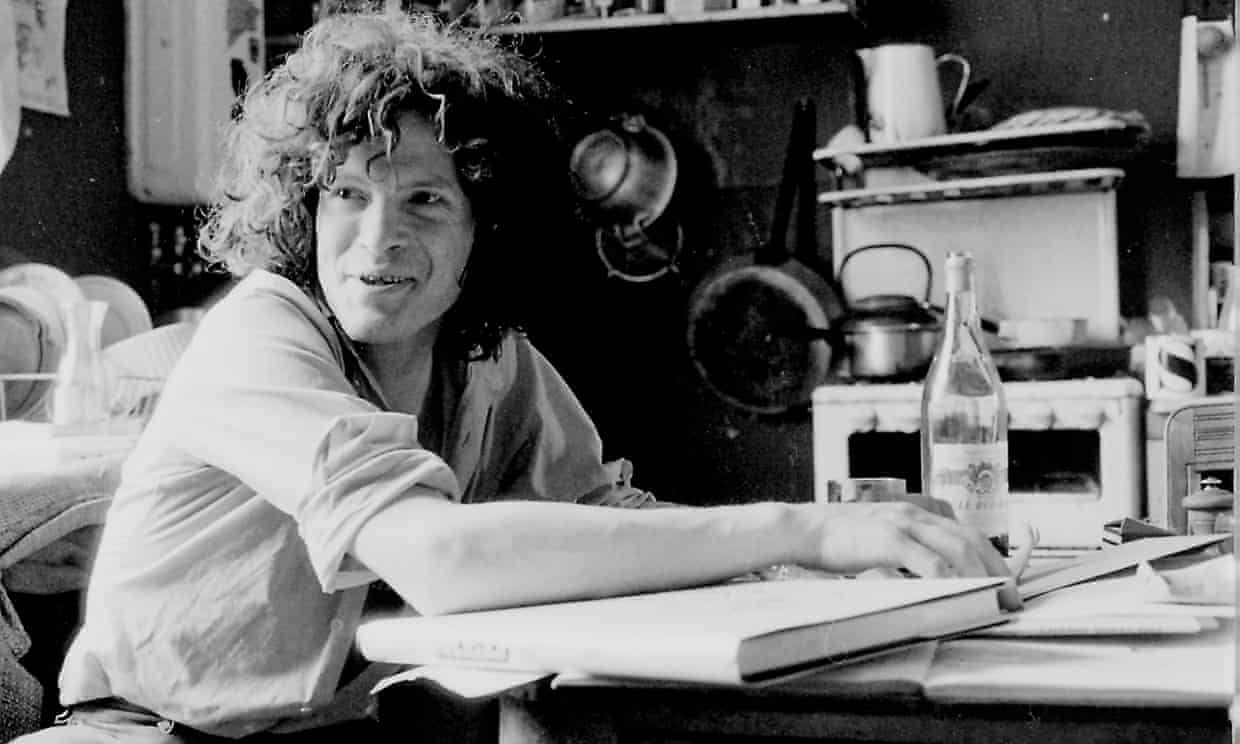

Lisa Kaltenegger – image from The Guardian – shot by Naomi Haussmann/The Observer

The interest in things alien certainly kicked up in the twentieth century. Many of us grew up in the space age, witness to the first “Beep-Beep” from orbit, the first peopled orbiters, rapt in front of our televisions when mankind first set foot on the moon. Part of this experience is to be awash in the science fiction of our own and earlier ages, dreaming of strange other-world societies, fearful of invasion, eager to learn the lessons of advanced technology. Some were even impressed and excited enough by the technology and the optimism of the age to begin college careers with the dream of becoming aeronautical engineers, and designing some of the hardware of the future.

Earthrise – image from Wikipedia

But so much of this was based on fantasy, (including that engineering thing) limited to imagining what might exist out there. Even the early observations of other planets in the solar system generated fantasies in addition to scientific elucidation. But in 1995 scientists discovered the first two exoplanets, and new discoveries are now a nearly daily event. Today, because of the major advances that we have made in telescope technology, we are able to see to the far ends of the universe. Enter Lisa Kaltenegger, founder and head of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University

I spend my days trying to figure out how to find life on alien worlds, working with teams of tenacious scientists who, with much creativity and enthusiasm and, often, little sleep but lots of coffee, are building the uniquely specialized toolkit for our search.

In studying what we have seen, it has become possible to detect stars that have planets around them. In fact, most stars have company. The way this is detected is to measure “wobble” in the light being observed from distant places. As if you were looking at a bright light and someone threw a ball across your field of view. The measured light would change and you could tell that something had been there. Keep looking to see if it repeats. If it does, then you probably have a planet orbiting that star. (or an annoying neighbor tossing something back and forth in front of you) Keep pointing the James Webb Space Telescope (the state of the art in telescopy today) to more and more locations in space. And discover more and more planets.

Jupiter – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

Kaltenegger has been looking into the reality of other worlds her entire career, and in doing so, has advanced our knowledge base considerably. She begins this book with a brief visit to an other planet, one that is very different from ours, a star-facing world that has portions in eternal day, night, and dusk, and local life adapted to the local venues, just to get things started on what we might expect out there, just to challenge our assumptions.

HD 40307g – A Super Earth – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

She follows with a history of Mother Earth, noting major stops along the evolution of our favorite place. She notes how life might have formed, when, and how that event altered the atmosphere and even the color of our atmosphere. The sequence is important, as her discussion of our exoplanet dreams demonstrates that we are a prisoner of time. What we see with our telescopes (and eyes) arrived here on light, and light must travel at or below the universal speed limit. (a leisurely 186,282 miles per second) So, whatever we see from even a nearby star/planet system originated tens or hundreds of years go, or even billions for our more distant neighbors. Anything residents of out there might have seen of us (really only since we started sending signals into the ether maybe a hundred years ago) is quite dated relative to who and what we are today. Absent the invention of a Warp Drive of some sort, we are doomed to be always too far away in years and miles from other intelligent species. Well, maybe.

Venus – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

It is possible, I suppose, for a civilization with massive resources to send a desperate one-way mission to save their species from hundreds of light years away. It is unlikely that any visitors from such distant realms would be making reports home. But this need not necessarily apply to all possible visitors. It appears that there are plenty of possible planets within a few light years of us that might present some interplanetary possibilities.

Mars – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

Kaltenegger delves into the nearer-earth planets, looks at their characteristics, and offers explanations as to their suitability for life. She looks at probable communication issues should we ever come across an ET, suggesting it might be the equivalent of humans attempting to communicate with a jellyfish

Grand Tour – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

Kaltenegger and her team design computer simulations, based on the hard work of examining concrete materials, inert and biologic, and putting that intel into a database. Check the signature spectrum of every new world and compare it with the growing list of catalogued items.

Today, solving the puzzle of these new worlds requires using a wide range of tools like cultivating colorful biota in my biology lab, melting and tracing the glow from tiny lava worlds in my geology lab, developing strings of codes on my computer, and reaching back into the long history of Earth’s evolution for clues on what to search for. With our own Earth as our laboratory, we can test new ideas and counter challenges with data, inspired curiosity, and vision. This interaction between radiant photons, swirling gas, clouds, and dynamic surfaces driven by the strings of code within my computer, creates a symphony of possible worlds—some vibrant with a vast diversity of life, others desolate and barren.

She notes the core need of life-sustaining planets is to be rocky. Sorry, Jupiter, no gas giants need apply (but their moons might). They also need to be within a certain range of the stars they circle, the so-called “Goldilocks Zone,” not so close as to be too hot nor so distant as to be too cold, and they need to show the presence of key life-sustaining elements.

Europa – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

Kaltenegger offers readers info on some topics likely to be new to most of us, Stellar Corpses, for example, warm ice, the Fermi Paradox, the Drake Equation, the Great Silence, tardigraves, and plenty more. All of these are explained clearly and simply. It is as if the author is telling us: This is what we have learned. This is what we expect. This is how we go about gathering information, fusing our fields of expertise, learning more, solving the mysteries that the data present. This is our understanding of what is possible. This is our plan for looking further and farther.

Trappist – image from Exoplanet Travel Bureau – NASA

Alien Earths may not point to an actual catalog of life-sustaining exoplanets, but it does offer an accessible pop-science portrait of the current state of the art in the search. This galactic age of exploration has been ongoing for some time, getting a jolt from the discovery of other worlds. It has advanced to where we are now looking for (and expecting to find) evidence of life on other planets. It is likely that what we find will be pretty basic, single-cell critters, maybe even plant life. And it will probably take a good long time before we can move up to the final phase of the game, finding intelligent life. The time scale for any potential interaction is likely to be considerable, but who knows? The universe is full of surprises among its billions and billions of stars.

So far, despite wild claims to the contrary, we have not found any definitive proof of life on other planets. Until we do, we will continue to improve our toolkit and look for signs of alien life the hard way: searching planet by planet and moon by moon.

Review posted – 09/27/24

Publication date – 04/16/24

I received an ARE of Alien Earths from St. Martin’s Press in return for a fair review. Thanks, folks, and thanks to NetGalley for facilitating.

This review is cross-posted on Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal, FB, Instagram, and Twitter pages

Interviews

—–We live in a golden time of exploration’: astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger on the hunt for signs of extraterrestrial life by Emma Beddington

—–Chris Evans Breakfast Show – Lisa Kaltenegger: Is There Alien Life? – Video – 25:39

—–StarTalk – Distant Aliens and Space Dinosaurs – with Neil DeGrasse Tyson – audio – 50:03

—–StarTalk – Astrophysicists Discuss Whether JWST Discovered Alien Exoplanets – Neil DeGrasse Tyson – video – 48:58

Item of Interest from the author

—–Lisa Kaltenegger. On Looking for Signs of life – Video – 10:36

Items of Interest

—–NASA – Jet Propulsion Laboratory – Visions of the Future

—–The Carl Sagan Institute

—–Unilad.com – NASA discovered -planet bigger than Earth with a ‘gas that is only produced by life’

Song

—–Monty Python’s Galaxy Song

=

=

All right, USA, who wants to go first? Come on, come on someone, anyone. Let’s see some hands. No? No one? All right then, Mother Nature will just have to choose one of you. Eenie meenie, miney mo, which will be the first to go? All right, Tangier Island, looks like you’re it. Congratulations! You are the premier official global warming refugee site in America. Come on down and receive your prize. Free ferry tickets to the mainland. Don’t let the waves hit you on your way out.

All right, USA, who wants to go first? Come on, come on someone, anyone. Let’s see some hands. No? No one? All right then, Mother Nature will just have to choose one of you. Eenie meenie, miney mo, which will be the first to go? All right, Tangier Island, looks like you’re it. Congratulations! You are the premier official global warming refugee site in America. Come on down and receive your prize. Free ferry tickets to the mainland. Don’t let the waves hit you on your way out.

There was a time when millions of us roamed the continent. We fed when there was need. We played in forests and open places. Our kind lived well, from the warm woodlands of the south to the frosty forests of the north and in the gentler landscapes between. We raised our pups in cozy dens, and raised our voices at night to call out to others. Sometimes, we joined our brothers and sisters in joyous chorus for no reason at all. We lived in a world with many others, hunters, prey, and creatures who seemed to have no great part of our existence. There were people here then. We lived with them, too. But other people came, people with guns, poison, and traps, people armed with fear, hatred, and ignorance. They took our food sources, and when we were forced to look elsewhere to feed, they turned their quivering, murderous hearts toward us. And there came a time when there were practically none of us left across the entire land.

There was a time when millions of us roamed the continent. We fed when there was need. We played in forests and open places. Our kind lived well, from the warm woodlands of the south to the frosty forests of the north and in the gentler landscapes between. We raised our pups in cozy dens, and raised our voices at night to call out to others. Sometimes, we joined our brothers and sisters in joyous chorus for no reason at all. We lived in a world with many others, hunters, prey, and creatures who seemed to have no great part of our existence. There were people here then. We lived with them, too. But other people came, people with guns, poison, and traps, people armed with fear, hatred, and ignorance. They took our food sources, and when we were forced to look elsewhere to feed, they turned their quivering, murderous hearts toward us. And there came a time when there were practically none of us left across the entire land.