Perseus…has no interest in the well being of any creature if it impedes his desire to do whatever he wants. He is a vicious little thug and the sooner you grasp that, and stop thinking of him as a brave boy hero, the closer you’ll be to understanding what actually happened.

Who decides what is a monster?

When Natalie Haynes wrote Pandora’s Jar, a collection of ten essays on the women in Greek myths, she included a chapter on Medusa. In nine-thousand words she offered a non-standard view of the story of heroic Perseus slaying the gorgon. But the story stayed with her, well, the rage about the story of how ill-treated this supposed monster had been, anyway. If the feeling remained that powerful for so long, it was a message. She needed to devote a full book to this outrage in order to get any peace. Thus Stone Blind.

Natalie Haynes – image from Hay Festival

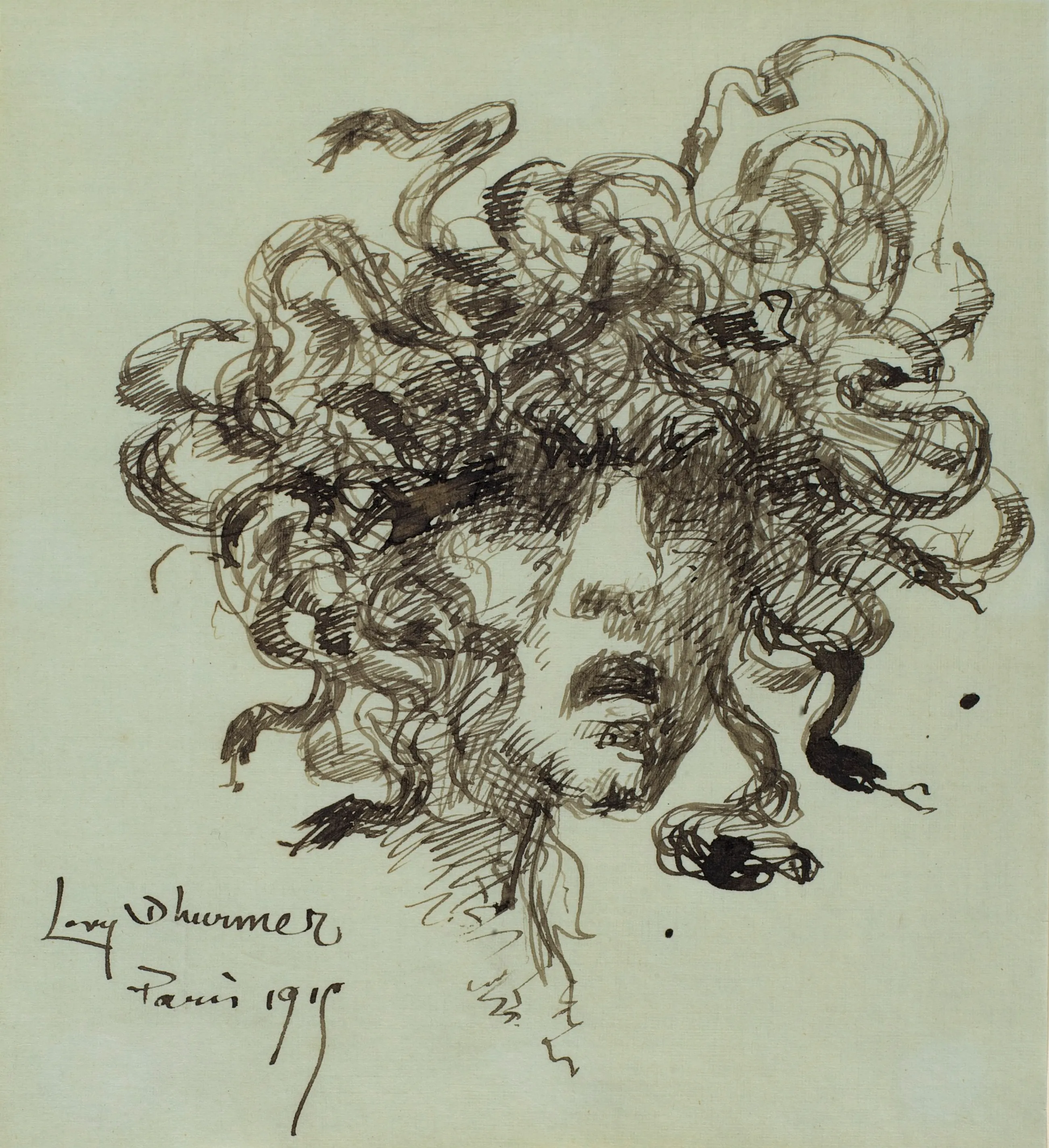

We learn how Medusa came by her notable do. After being sexually assaulted by Poseidon in one of Athena’s temples, the goddess was appalled. No, not by the rape. I mean a god’s gotta do what a god’s gotta do. But that he raped Medusa in Athena’s temple! Desecration! Well, that cannot go unpunished. So, Athena seeks revenge on Poseidon by assaulting Medusa, figuring, we guess, that this might make Poseidon sad, or something. Uses her goddess powers to turn Medusa’s hair to snakes and her eyes to weapons of mass destruction. Any living creature she looks at will be lithified.

Image from Mythopedia – Head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens – 1618

Then there is the other half of this tale, Perseus. We are treated to his dodgy beginnings, another godly sexual assault. He is not portrayed here as the hero so many ancient writings proclaim. Decent enough kid, living with his mom, Danae, and a stepfather sort, until mom is threatened with being forcibly married to the local king, a total douche. Junior tries to make a deal to get her out of it, said douche sending him on a seemingly impossible quest. Good luck, kid. I mean, seriously, how in hell can he hope to bring back a gorgon’s head?

Image from Ancient Origins

Zeus feels a need to help the kid out. I mean, Perseus may be a bastard, but hey, in Greek mythology, that would put him in the majority. Am I right? Still, he is Zeus’s bastard, so Pop does what he can to help him out, sending along two gods to coach and aid the lad as needed. Hermes and Athena snark all over Perseus, pointing out his many weaknesses and flaws, while providing some very real assistance. They may not hold the kid in high regard, but neither can they piss off the boss. Very high school gym, and totally hilarious.

Image from Wiki – Perseus Turning Phineus and his followers to stone by Luca Giordano – 1680s

Which should not be terribly surprising. Haynes is not just an author and classicist, but a stand-up comedian. You can glean what you need to know about her comedic career from the Historical Archivist interview linked in EXTRA STUFF. There is plenty of humor beside godly dissing of Perseus. Athena (referred to as Athene in the book) tries to talk an unnamed mortal into signing on to a huge battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants, new powerhouse versus the current champs. It is clearly a tough sell.

‘If you get trodden on by a giant or a god – which wouldn’t be intentional on our part, incidentally – but in the heat of battle one of us might step in the wrong place and there you’d be. . . . Well, would have been. Anyway, it would be painless. Probably very painful just before it was painless, but not for long.’… ‘Come on. If you do die, I’ll put in a word for you to get a constellation. Promise.’

There are plenty more like these, including a particularly shocking approach to relieving a really bad headache.

Image from Scary For Kids (reminds me of the nun I had for eighth grade)

But the whole quest experience uncovers Perseus’s inner god-like inclinations. He becomes an entitled rich kid with far too many high-powered connections helping him out. And develops a taste for slaughter. When Andromeda sees a knight in shining armor, come to save her from certain death by sea monster, her parents suggest that “Maybe, Sweetie, you might consider how gleeful he was when he was murdering defenseless people?” Or noting that if he had really been solid on keeping promises he might have headed straight home to save his mom with that snaky head instead of stopping off to frolic in blood for a few days. “This boy’s gonna be trouble, Andy.”

Image from Classical Literature

The gods have issues. The Housewives of Olympus could well include some unspeakable husbands, who seem to have a thing for forcing themselves on whomever (or whatever) catches their eye. As a group they are always on the lookout for slights, insults, or minor border transgressions. What a bunch of whiny bitches! But with power, unfortunately, to make life unspeakable for us mere mortals, whose life expectancy is not even a rounding error to their eternal foolishness. Medusa, in that way, was one of us. There is uncertainty about Perseus.

Image from Talking Humanities

Sisters abound. Apparently, triple-sister deities was a thing for the ancient Greeks. We are treated to POVs from Medusa’s two gorgon sibs, and look on as Perseus hoodwinks the three hapless Graiai sisters, who are doomed to having to share a single eye and a single tooth among them. (Could you please wipe that thing off before you pass it along?) The Nereids are more numerous (50) and a bit of a dark force here.

From Greek Legends and Myths – by Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901)

Never one to stick to a single POV, Haynes offers us many discrete perspectives over seventy-five chapters. Fifteen are one-offs. The Gorgoneion leads the pack with thirteen chapters, followed by Athene with eleven, Andromeda with eight and Medusa with seven. There are some unusual POVs in the mix, a talking head (no, not David Byrne), a crow, and an olive tree among them. Haynes dips into omniscient narrator mode for a handful of chapters as well.

Image From Empire

As noted in EXTRA STUFF, there is a particularly offensive sculpture of Perseus holding Medusa’s severed head. Not only has he murdered her, he is standing on her corpse. You can see how this would piss off a classicist who knows that Medusa never hurt anyone. Damage done by her death-gaze was inadvertent or done by others using her head as a weapon. And this supposedly brave warrior killed this woman in her sleep. Studly, no? And with all sorts of magical help from his father’s peeps. What a guy!

Image from Smithsonian American art Museum – by Lucien Levy-Dhurmer – 1915

Natalie Haynes set out to tell Medusa’s story, and it is completely clear by the end that the monstrosity here is the treatment this innocent female mortal received, at the hands of abusers both male and female. Haynes keeps the story rolling with the diverse perspectives and short chapters, so that even if you remember most of the classic myth there will be plenty of mythological history you never knew. You will also laugh out loud, which is a pretty good trick for what is really a #METOO novel. The abuse of the powerless, of women in particular, by the powerful has been going on only forever. Haynes has made clear just how the stories we have told for thousands of years reinforce, and even celebrate, that abuse. Next up for her, fiction-wise, is Medea. I can’t wait.

Image from Smithsonian American Art Museum – by Alice Pike Barney – 1892

Medusa may not have been a goddess, but it seems quite clear that Natalie Haynes is. This is a wonderful read, not to be missed.

He’s just a bag of meat wandering round, irritating people.’

Review posted – 02/24/23

Publication dates – Hardcover

———-UK – September 15, 2022 Mantle

———-USA – February 7, 2021 – Harper

This review has been cross-posted on GoodReads. Stop by and say Hi!

Image from Wiki by Caravaggio – 1597

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal, Twitter and Instagram pages

Interviews

—–The Bookseller – Natalie Haynes on challenging patriarchal historical narratives and championing female voices by Alice O’Keeffe

—–CBC – Natalie Haynes on the fantastic and fearsome women of Greek myth

—–LDJ Historical Archivist – Brick Classicist of the Year 2023 Natalie Haynes – video – 16:46 – this is delicious

—–Harvard Bookstore – Natalie Haynes discusses “Stone Blind” – video 1:03:55 – – This is amazing! So much info. You will learn a lot here.

My review of other work by the author

—–2021 (USA) – A Thousand Ships – Helen of Troy and the women of the Homeric epics

Items of Interest

—–Wiki on Gorgoneion

—–The Page 69 Test – Stone Blind – a bit of fluff

—–Widewalls – An Icon of Justice – Or Something Else? A New Medusa in a NYC Park – interesting contemporary sculptural response to a classical outrage.

Left: Benvenuto Cellini – Perseus holding the head of Medusa, 1545–1554. Image creative commons / Right: Luciano Garbati – Medusa With The Head of Perseus, 2008-2020. Installed at Collect Pond Park. Courtesy of MWTH Project – images and text from Widewalls article

The MWTH (Medusa with the head) image is sometimes accompanied by the ff: “Be thankful we only want equality and not payback.”