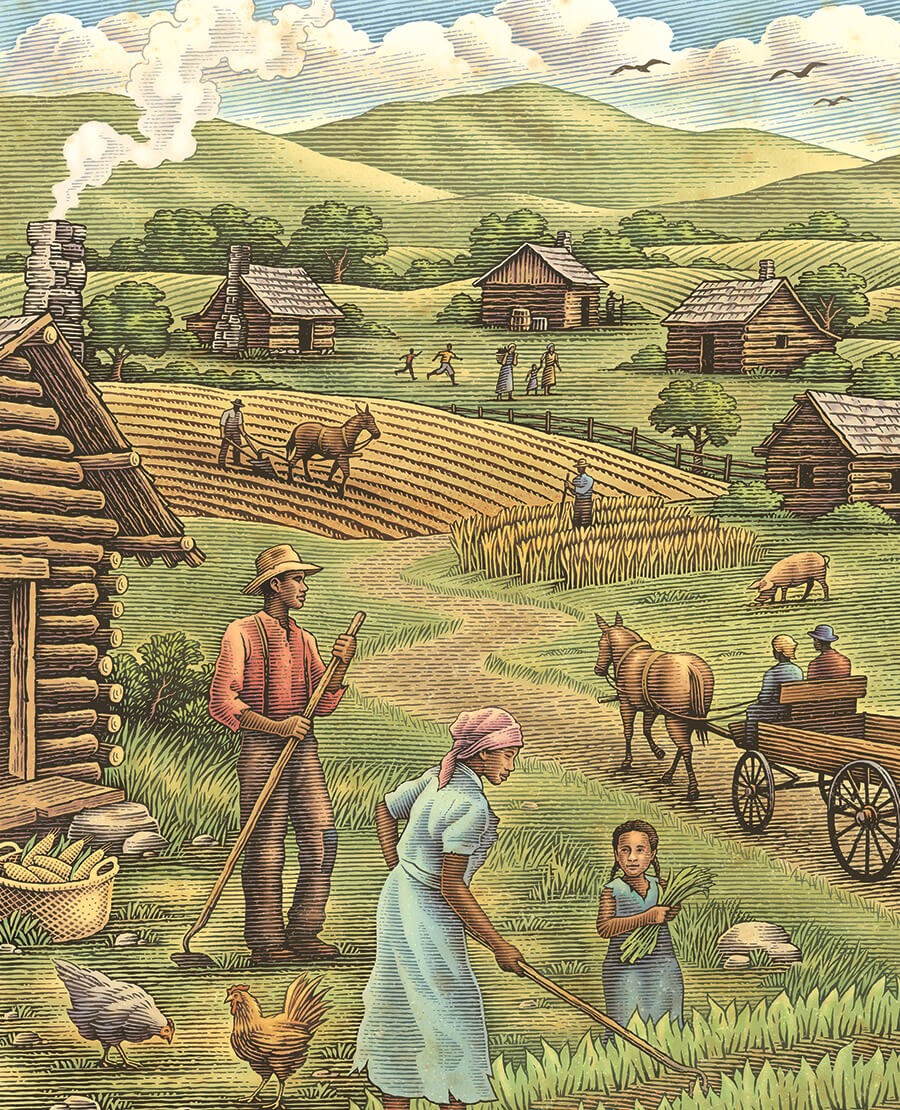

At age one, Gabriel Fisher weighed thirty-four pounds and stood forty-one inches tall. It was not only Gabriel’s unusual size that dazzled Thomas, but also his unusual way with animals. As a three-year-old boy, Gabriel would often sit on a milking stool beside Jasper’s chicken coop with a piece of bread hidden behind his back. He’d wait, watching the chickens scratch in the yard until his favorite hen, a barred rock named Betsy, eased her way close to his feet, and then he’d reveal the bread with a flourish. The other hens would race toward him, but Betsy would immediately hop on his lap and peck at the bread until she’d eaten it all. Afterward, Gabriel would cuddle her while he napped in the afternoon sunshine, and she’d turn her beak into the hollow under his armpit and fall asleep.

I recognized myself inside those pages. In a life devoted to goodness, devoted to God, there can still be yearning. A quiet mouth, a devoted heart, does not mean a quiet mind. Sometimes while reading, I found myself crying, overwhelmed by the depth and breadth of Miss Dickinson’s daring, by the baring of her soul.

Some books you rip through, eager, panting, for the resolution of a conflict and the presentation of the next one. Some books demand that you go through them slowly, a stroll hand in hand. Instead of a 5K. Life, and Death, and Giants is a book you want to take your time with, savor, taste, relish, feel.

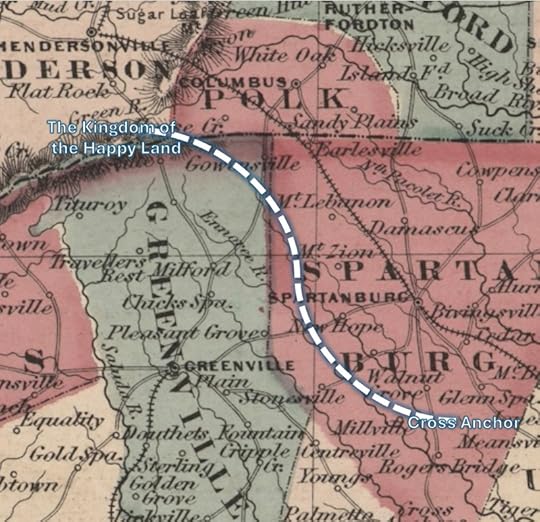

Ron Rindo – image from Wisconsin Literary Map

Ron Rindo came across the story of the tallest person ever, from the 1920s and 1930s, and wondered how the modern world might react to a someone of like dimensions.

Just eight pounds five ounces at birth, [Robert Pershing] Wadlow stood eight feet 11.1 inches tall, weighed 439 pounds, and had size 37 feet at the time of his death, at age twenty-two, his extraordinary growth driven by hypertrophy of the pituitary gland. For a time, Wadlow toured with the Ringling Brothers Circus and promoted shoes for the International Shoe Company, but he seems to have sought a normal life, resisting efforts to define him exclusively as a circus attraction. He died of an infection in Manistee, Michigan, and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Alton, Illinois. My musings about how the twenty-first-century world might react to a giant in its midst provided the initial inspiration for this novel. – from the Acknowledgments

Giants such as these may have a brief stay among us, but, unlike the “beetle at the candle” or the “Hopper of the mill” can maintain more than their mere accidental existence. (The title of the novel is taken from that of the poem by Emily Dickinson. There is a link to it in EXTRA STUFF.) Gabriel Fisher is a magical person, imbued with qualities of a different realm. It is not just his physical characteristics, which mimic those of an actual human being, or the athletic prowess that traveled with his inflated size, but his kindness, considerateness, his gentleness, and his Franciscan affinity for creatures wild and domestic. A Tom Bombadil comparison would also be apt.

He opened his mouth, bayed like a young coyote. “That’s the boy,” Thomas said, smiling. “Let everyone know you’re here.” From the woods just beyond Thomas’s yard, a red fox barked, and squirrels began chattering. A half mile down the road, farm dogs howled; cattle lowed in their sunny pastures.

But, as great a presence as Gabriel is, it is the other characters in the novel who tell us what we need to know about him. He is a central hub around whom all the character spokes attach and it is their stories that make the novel roll.

“It’s a polyphonic novel, told from multiple perspectives, so in a sense, it’s five different stories,” says Rindo. “Hannah, Doc Kennedy, Billy Walton and Trey Beathards tell Gabriel’s story, but in the process, each of them tell their own story, too.” – from the Madison Magazine interview

Hannah Fisher is Gabriel’s grandmother. She loves him unreservedly, but the code of her Amish religion keeps her at a distance for far too long. Gabriel was born out of wedlock, his mother, who dies in childbirth, shunned by the community. Hers is one of the primary voices we hear throughout, as she struggles with the tensions between her faith, her love, and her sense of right and wrong.

Dr. Thomas Kennedy is a veterinarian, and the other primary voice here. Tragedy and unwarranted suspicion had driven him from a more urban life to this rustic town of Lakota, Wisconsin. He forms a life-time bond with Gabriel by virtue of delivering him into the world. Their connection is a thing of beauty, and will warm your heart. He also nurtures a friendship with Hannah. He is as good a person as you will come across anywhere.

Billy Walton manages a youth baseball team, and recruits the very oversized Gabriel to sign on. He is, of course a marvelous and dangerous player, given his power. Billy owns the local bar, and is making a place for himself after a lifetime of screwups.

Trey Beathards used to be someone, a football player, later a coach, then a drug addict and womanizer. There is much of Trey that is in need to rebuilding. He becomes Gabriel’s high school football coach, and guides his next steps. Billy and Trey introduce us to the great sports myth piece of the novel as Gabriel’s prowess exceeds any reasonable expectation, becoming the stuff of legends.

Most of the primary life tales told here share an arc. A past with troubles, self-inflicted or not, then rising from their ashes to find hope, redemption, or something like it. It is in how the characters behave around Gabriel, how they help him, look after him, care about him that we see a community in action. I am trying not to say it takes a village, but it is unavoidable.

There is a set of secondary characters here who add to the community element of the story, a gay couple who take in a stray, a severe Amish husband who does not welcome any “English” influence, a crusty older Amish man who seems to have burned all his bridges, a brotherly caretaker who goes above and beyond in caring for another.

The lines between Amish and “English” can be difficult to traverse, but Gabriel has a foot in both worlds and helps bring them to a common cause. In a different way, Thomas tries to expose Hannah to possibilities beyond her Amish restrictions. Rindo’s handling of religious and secular perspectives is deft.

You will enjoy the occasional book references scattered throughout, both to specific novels and to other unnamed texts. In parallel with the split between seeking fame versus opting for retreat, there is the tension between looking outward for inspiration and looking inward.

In his day job, Rindo teaches, among other things, the poetry of Emily Dickinson. That appreciation makes its way into the novel in two forms, a book of Dickinson’s poems that Hannah’s mother had left for her, and work left by another maternal influence. The poet’s perspective is woven into the tale, in a concern for faith, for nature ,and for the struggle to figure out how to live one’s best life, alone and in community, and the many sorts of love one can enjoy.

There were multiple times while reading this book that I was moved to tears. Not just for the emotional content of the characters’ struggles, but for the poetic descriptions, particularly of natural events.

Sometimes we feel we are on the scent of hidden things, but we doubt ourselves. Sometimes it’s because we believe we must be mistaken. Other times, it’s because we fear we might be right and we don’t want to be, or can’t be, because of who we are or where we live. But then something comes along to reveal that what we have scented with our innermost soul simply is, and our fear subsides. This revelation was my mother’s legacy, a book of poems she’d hidden, like a pheasant in the orchard grass.

There is no need to fear anything here. Life, and Death, and Giants is a heart-warming novel that will bring tears to your eyes, but which will also prompt you to consider just how to live, and just how society might work with a baseline of respect. It is one of the great works of 2025.

Review posted – 09/12/25

Publication date – 9/9/25

I received an ARE of Life, and Death, and Giants from St. Martin’s in return for a fair review. Thanks, folks, and thanks to NetGalley for facilitating.

This review is cross-posted on Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

==================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to Rindo’s personal and Instagram pages

Profile – from Wisconsin Literary Map

An English professor at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Ron Rindo was raised in Muskego, Wisconsin, and lives with his wife, Jenna, on five acres of wooded land in Pickett, where they raised five children and keep an orchard and an array of vegetable and flower gardens. He has published three short story collections, Suburban Metaphysics and Other Stories (New Rivers Press, 1990); Secrets Men Keep (New Rivers Press, 1995); and Love in an Expanding Universe (New Rivers Press, 2005); and a novel, Breathing Lake Superior (Brick Mantel Books, 2022). His short stories and essays have also appeared in a wide variety of journals, and an essay, “Gyromancy,” was reprinted in The Best American Essays, 2010

Interviews

—–ABC National Radio – Greyhounds, dark academia and an Amish community in new fiction by Toni Jordan, R.F. Kuang and Ron Rindo – audio – from 37:22

—–Madison Magazine – This novel set in small-town Wisconsin is more than a ‘tall tale’ by Anna Kottakis

Music

—–Hungarian Rhapsody Number 2 – in Chapter 8

Items of Interest from the author – Links to these short stories can also be found in Rindo’s website

—–Terrain.org – The Return of Migrating Birds

—–The Summerset Review – Horses

—–Wilderness House Literary Review – The Mystery in Summer Rain

—– The Trumpeter – The Song of the Tree Frog

—–Tikkun – A Theory of Everything

Items of Interest

—–All Poetry – Life, and Death, and Giants

—– Eddie Carmel

For what it’s worth, I had the experience, growing up in the West Bronx, of seeing Eddie Carmel every now and again. He and his parents lived there. It’s not like we ever had a conversation. But my pals and I spotted him climbing into a taxi or other car, feet planted in the front passenger seat. Tush in the rear. At that time of his life, he was afflicted with scoliosis, among other maladies, and walked with at least one cane. While it was startling to see someone that large (believe the 8’9″ number. There is no way he was only 7’3″) it was also very sad. It seemed from looking at him, his face, that this was a man who was in great pain. He was someone who was no longer able, if he had ever been able, to be comfortable in his own oversized skin. Awe was replaced with a very large feeling of pity.

” alt=”book cover” width=”187″ height=”300″ align=”left” hspace=”10″ vspace=”10″>

” alt=”book cover” width=”187″ height=”300″ align=”left” hspace=”10″ vspace=”10″>