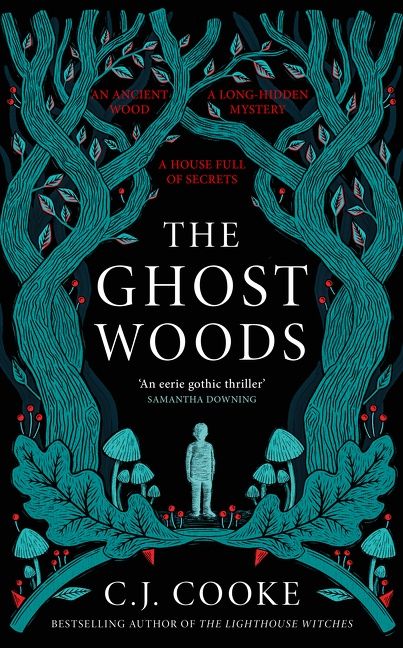

Oh God, there it is, lit up by the car’s headlights. Four pointy turrets and dark stone walls laced with red ivy. It looks like Dracula’s holiday home.

Something unspeakably evil is stalking the grounds of Lichen Hall.

Two women, from different backgrounds, at different times, (1959 and 1965) find themselves in the same position, pregnant without a mate in a period in which that was not considered socially acceptable. Such women were often shunted off to mother-and-baby homes. You may have heard of the Madgalene laundries of Ireland. They were awful, and were not restricted to the Emerald Isle. But Mrs. Whitlock’s Lichen House is soooooo much worse. There is plenty of strangeness about the place and some of its inhabitants, well beyond garden-variety human unpleasantness.

C.J. Cooke – image from Curtis Brown

In 1959, seventeen-year-old Mabel Anne Haggith finds herself five months deep in a family way, despite never having had sex. Her mother and stepfather have sent her off to be seen to, out of sight of the neighbors. She is truly a clueless innocent. She feels that there are ghosts in her body. In 1965 Pearl Gotham, twenty-two, a nurse, is likewise facing emerging problems, an unreliable bf among them. Both are taken in by the welcoming, if somewhat chilly, Mrs. Whitlock. The house seems likelier to generate nightmares than comfort to women in need. In fact, it has much in common with the abusive mother-and-baby institutions of its time. More about that later.

Mabel is very much a pleaser, eager to fit in, even when hazed by those already there. She is shy and unsure of herself, working class, uneducated, and for all intents and purposed alone in the world. Until she finds a friend in another young woman there, Morven.

Pearl arrives with much more confidence. A nurse, she is aware of the seriousness of the lack of real medical care at Lichen House. She is also much more worldly, more socially able, not just with the other young women but with Mrs. Whitlock as well. In addition she is charged with tutoring Mrs. Whitlock’s decidedly odd grandson.

Cooke offers a cornucopia of detail that gives the creepiness texture and provides a constant source of surprising revelations. There are mysteries to be sussed out. The overarching imagery of the story has to do with fungi. The house itself is seriously infested with molds of various sorts, and is rapidly sinking into decrepitude.

I follow her gaze to an enormous mass of yellow fungus creeping up the side of a wall. What looks like a series of giant ears are bulging from the gap in the doorframe, right down to the floor. As I draw my eye across the length of the vestibule I spot more fungus spewing from cracks in the tiles and the window frames. The vaulted ceiling is sullied by black blooms of mold. Black frills poke out from the wooden steps at my feet. And at the end of the staircase, a plume of honey-gold mushrooms nub out from the newel post, perfectly formed. It makes me feel physically ill.

“What happened?” I ask, burying my mouth in the crook of my arm.

She sighs wearily. “An infestation of fungus. I still can’t quite believe it. This house has been standing for four hundred years. It has withstood bombs, floods, and a bolt of lightning.” She folds her arms, exasperated. “Fungus can eat through rock, can you believe that?”

“Good God,” I say.

The woods manifest spots of light that can lure one in. Mrs. Whitlock celebrates every birth with a puff of fairy dust toward the newbie. Mr. Whitlock maintains a Micrarium, a sort of mini- museum, a cabinet of curiosities focused on fungi. He makes a big deal about cordyceps, which may be familiar to fans of The Last of Us.

There is plenty of strangeness. Who posts a “Help Me” poster in one of the rooms? Who is that little boy Pearl sees dashing about, the one the other young women deny having seen? Mrs. Whitlock seems particularly averse to making use of the medical profession, forcing her guests to give birth in the house, with only the assistance of the women living there. What’s up with that? Mr. And Mrs. Whitlock were reputed to have had a son who died in an auto accident, but his body was never recovered. Huh? Who is the mysterious, threatening figure in the woods?

“So there’s a story about a witch who lives in the ghost woods out in the forest.”

“I’ve heard of that,” I say. “Mrs. Whitlock mentioned it. At least, the ghost woods part. I don’t believe she mentioned a witch.”

“Well, I heard about it when I first came here,” Rahmi says, and I see Aretta give her a look, as though to warn her not to say more. Rahmi notices, and bites back whatever she was going to say. “I’ve seen her,” she says guardedly.

“Who, the witch?” I say, and she nods. I study her face, expecting her to say “Boo!” or something, revealing it all as a big joke.

“Well, then,” I say, raising my glass of water as though it is a crisp Chardonnay. “I shall seek out this witch in the ghost woods. A little bit of spookiness will spice this place up nicely.”

“Don’t,” Rahmi says, though I’m not sure how much I should take this at face value. “It might be the last thing you ever do.”

As the story goes, Nicnevin was a witch who had lain with a girl who had fallen asleep in the woods. When the girl gave birth, it was to a monstrosity, and it was killed. Nicnevin made the family mad before killing them, then took over the family hall to be a place of rot and ruin, naming it Lichen Hall.

In addition to the ample gothicness of the novel, there is plenty of character and plot content to keep you flipping those pages, and maybe loading up on bleach. Both Mabel and Pearl are sympathetic. What will happen with them, with their babies? What kind of danger are they in? You will definitely care.

There is also plenty of payload beneath the overlaid story. In an image of how women were treated in the 50s and 60s, the awfulness of Mrs. Whitlock’s Lichen House offers a vibrant image of a decaying institution, controlled by ill-meaning people, enforcing wrong-headed social norms, and crushing any people or behaviors falling outside the prescribed lanes. It is a moving, powerful, effective tale.

The Ghost Woods is, first and foremost, a gothic novel, the last installment of a thematic trio that considers our relationship with nature, motherhood, memory, and trauma (the previous two installments are The Nesting and The Lighthouse Witches). I suppose the question could legitimately be asked whether motherhood, gay rights, reproductive rights, and gender inequality have any place in a gothic novel. For me, the gothic is exactly the space to explore darkness of any kind, and the practice of othering is one of the darkest corners of human history. – from the Author’s Note

Review posted – 06/27/25

Publication date US trade paperback – 4/29/25

First published UK – hardcover – 10/13/22

I received an ARE of The Ghost Woods from Berkley in return for a fair review and a pinch of fairy dust. Thanks, folks, and thanks to NetGalley for facilitating.

This review is cross-posted on Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to Cooke’s personal, FB, Instagram, and Twitter pages

Her personal site was strangely unavailable when I was testing this. I am hoping it has been restored by the time you see this.

Profile – from GR

C.J. (Carolyn) Cooke is an acclaimed, award-winning poet, novelist and academic with numerous publications as Carolyn Jess-Cooke and Caro Carver. Her work has been published in twenty-three languages to date. Born in Belfast, C.J. has a PhD in Literature from Queen’s University, Belfast, and is currently Reader in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow, where she also researches the impact of motherhood on women’s writing and creative writing interventions for mental health. Her books have been reviewed in The New York Times, The Guardian, Good Housekeeping, and the Daily Mail. She has been nominated for an Edgar Award and an ITW Thriller Award, selected as Waterstones’ Paperback Book of the Year and a BBC 2 Pick, and has had two Book of the Month Club selections in the last year. She lives in Scotland with her husband and four children.

Interviews

—–Rachel Herron – Ep. 208: CJ Cooke on the Thrills of Contemporary Gothic Horror – video – 33:29 – begin at 8:10 – not specific to this book, but interesting

—– Murder by the Book – – C.J. Cooke in Conversation with Rachel Harrison

My review of prior work by Cooke

—–The Lighthouse Witches).

Songs/Music

—–The Beatles – I Want To Hold Your Hand – referenced in Chapter 2

Item of Interest from the author

—–Insta – CJ holds forth on the mother-and-baby homes theme from The Ghost Woods on her insta page

—– Google Play Books – Excerpt – audio – 10:36

Items of Interest

—–Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan – a great novel re the Magdalene laundries

—–Wiki – Magdalene laundries in Ireland

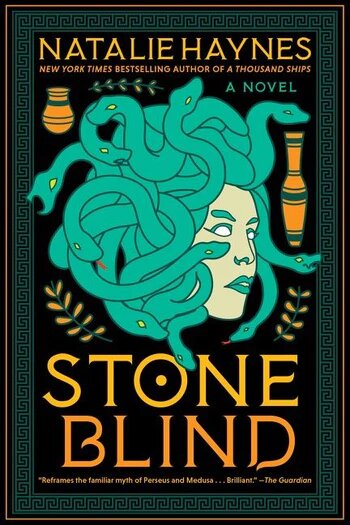

—–What Moves the Dead – another novel involving fungi