What makes a person the same person over time? Is it our consciousness, the what-it’s-like to be us? Is consciousness like a light that’s either on or off?

What remains of a person once they’ve died? It depends on what we choose to keep.

Amy Kurzweil is a long-time cartoonist for The New Yorker. If the name sounds a bit familiar, but you aren’t a reader of that magazine, it may be because her father is Ray Kurzweil. He is a genius of wide renown. He invented a way for computers to process text in almost any font, a major advance in making optical character recognition (OCR) a useful, and ubiquitous tool. He also developed early electronic instruments. As a teenager he wrote software that wrote music in the style of classical greats. No gray cells left behind there. He happened to be very interested in Artificial Intelligence (AI). It helps to have a specific project in mind when trying to develop new applications and ideas. Ray had one. His father, Fred, had died when he was a young man. Ray wanted to make an AI father, a Fred ChatBot, or Fredbot, to regain at least some of the time he had never had with his dad.

Amy Kurzweil – Image from NPR – shot by Melissa Leshnov

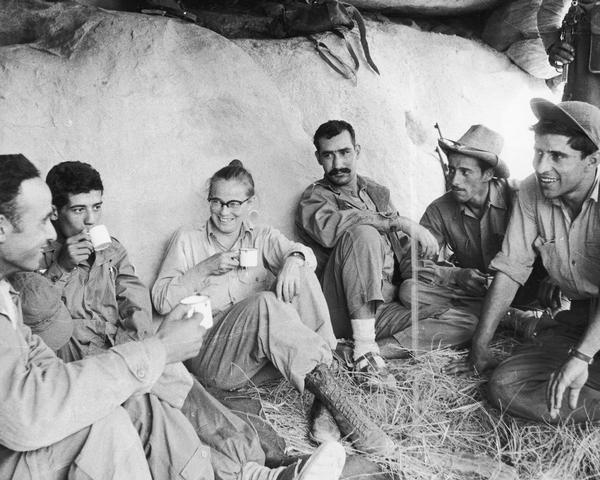

Fred was a concert pianist and conductor in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s. A wealthy American woman was so impressed with him that she told him that if he ever wanted to come to the USA, she would help. The Nazification of Austria made the need to leave urgent in 1938, so Fred fled with his wife, Hannah. (He had actually been Fritz in Austria, becoming Fred in the states.) He eventually found work, teaching music.

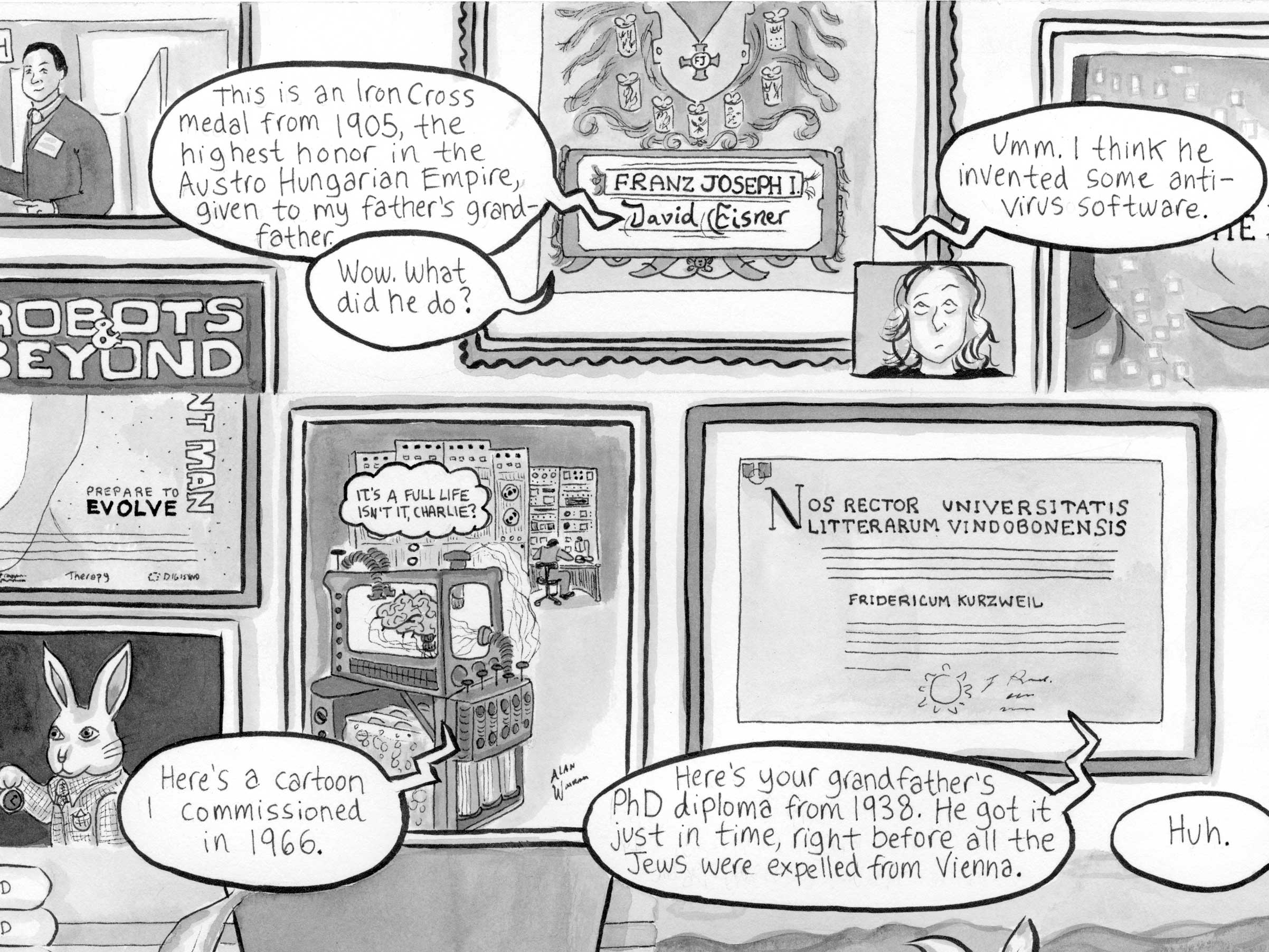

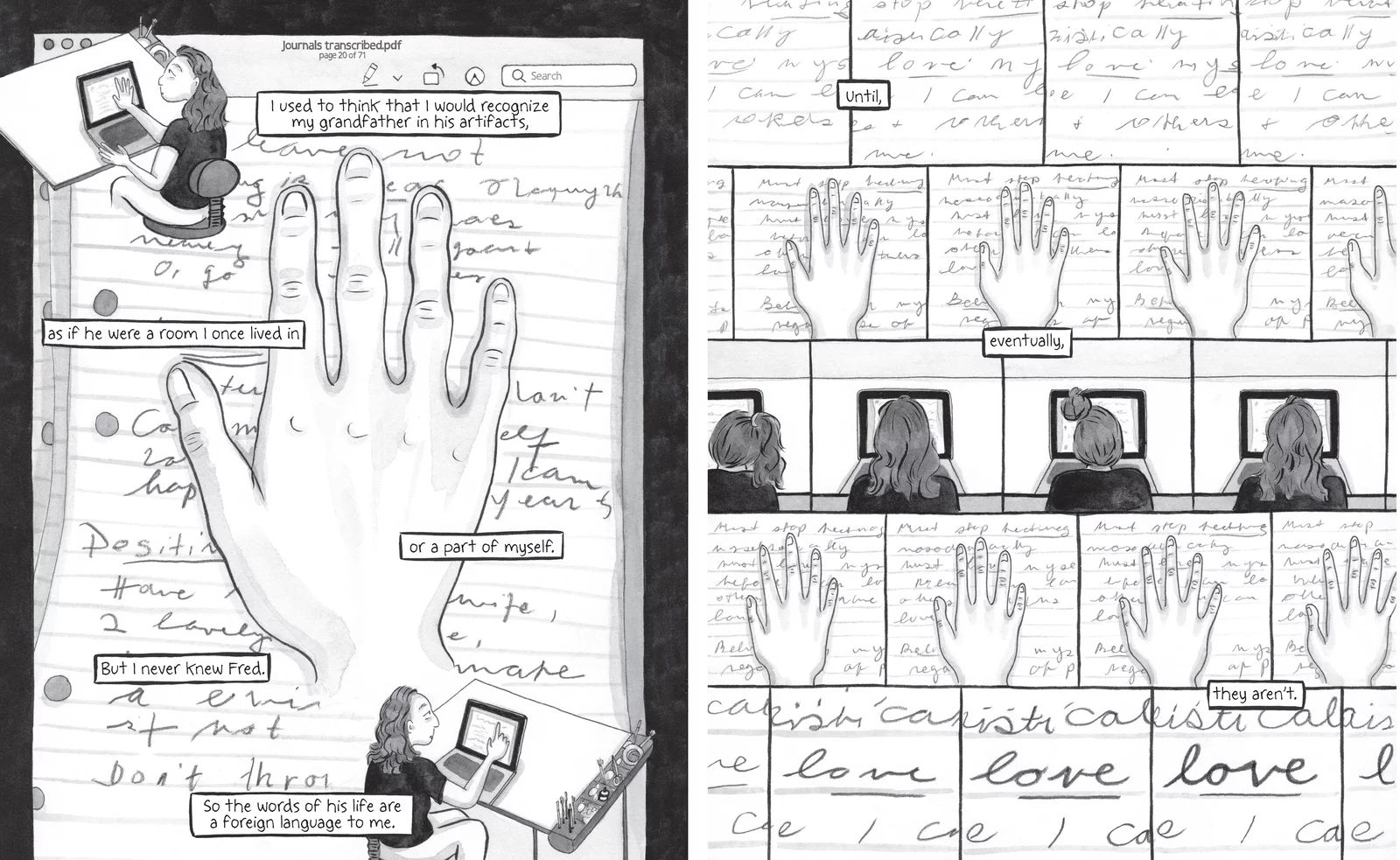

Artificial: A Love Story is a physically hefty art book, a tale told in drawings and text. Amy traces in pictures her father’s effort to reconstruct as much of his father’s patterns as possible. To aid in the effort there was a storage facility with vast amounts of material from his life both in Austria and in America. She joins into the enterprise of transcribing much of the handwritten material, then reading it into recordings which are used to teach/train the AI software. It is a years-long process, which is fascinating in its own right. She also draws copies of many of the documents she finds for use in the book.

Ray Kurzweil with a portrait of his father – image from The NPR interview – Shot by Melisssa Leshnov

But there is much more going on in this book than interesting, personalized tech. First, there is the element of historical preservation.

I always understood my father’s desire to resurrect his father’s identity as being connected to two different kinds of trauma. One is the loss of his father at a young age in a common but tragic scenario, with heart disease. The other trauma is this loss of a whole culture. Jewish life in Vienna was incredibly vibrant. Literally overnight it was lost. The suddenness of that loss was profound, and it took me a while to appreciate that. My great-aunt Dorit, who died this past year at 98, said they were following all the arbitrary protocols of the Nazis to save all this documentation. Saving documentation is an inheritance in my family that is a response to that traumatic circumstance. – from the PW interview

Kurzweil looks at three generations of creativity, (Fritz was a top-tier musician. His wife, Hannah, was an artist. Ray was also a musician, but mostly a tech genius. Amy is a cartoonist and a writer.) using Ray’s Fredbot project as the central pillar around which to organize an ongoing discussion of concepts. In doing so, she offers up not merely the work of the project, but her personal experiences, showing clear commonalities between herself and her never-met grandfather. This makes for a very satisfying read. Are the similarities across generations, this stream of creativity, the impact not just of DNA, but of lived experience? Nature or nurture, maybe the realization of potential brought to flower by the influence of environment whether external (living in a place that values what one has to offer) or internal (families nurturing favored traits)?

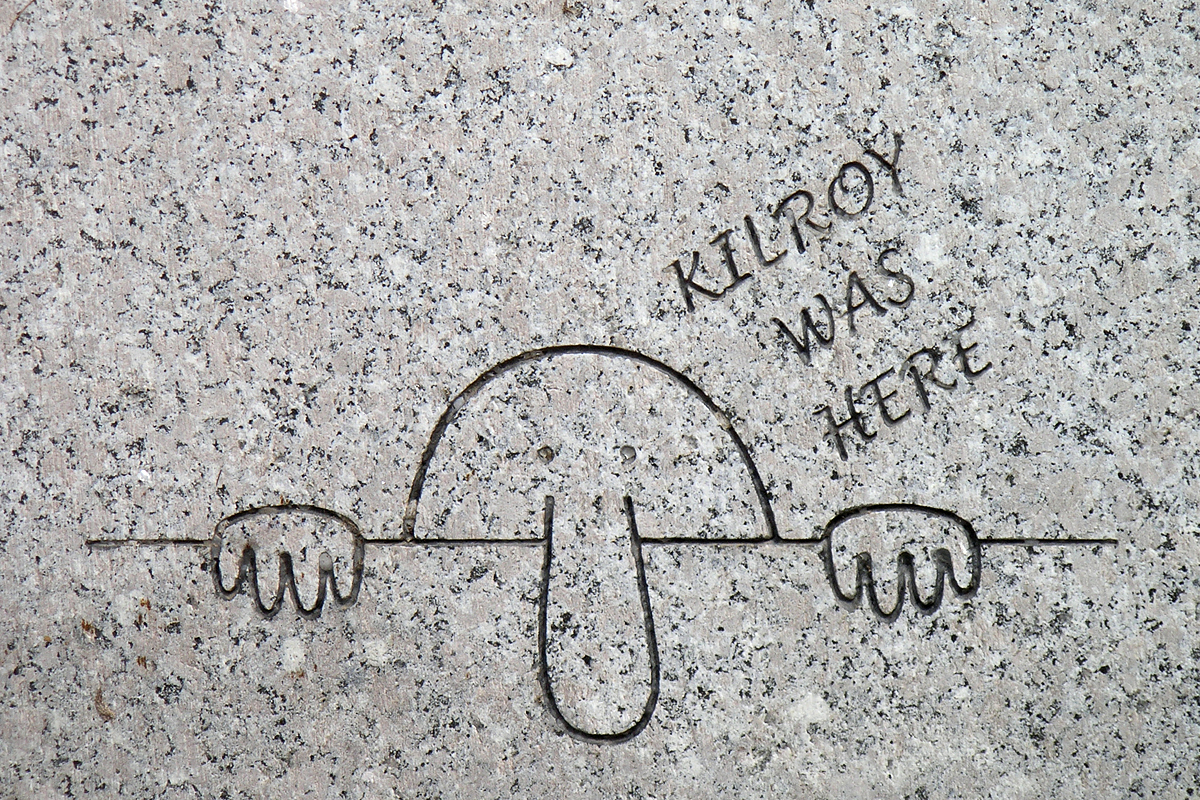

Image from the book – posted on The American Academy in Berlin site

One could ask, “what makes us what are?” The book opens with a conversation about the meaning of life. But life is surely less determinative, less hard-edge defined than that. A better question might be what were the historical factors and personal choices that contributed to the evolution of who we have become?

Image from the book – it was posted in the NPR interview

Existential questions abound, which makes this a brain-candy read of the first order. Kurzweil looks at issues around AI consciousness. Can artificial consciousness approach humanity without a body? What if we give an AI a body, with sensations? Ray thinks that we are mostly comprised of patterns. What if those patterns could be preserved, maybe popped into a new carrier. It definitely gets us into Battlestar Galactica territory. How would people be any different from Cylons then? Is there really a difference? Would that signal eternal life? Would we be gods to our creations? If we make an AI consciousness will it be to know, love, and serve us? The rest of that catechistic dictat adds that it is also to be happy with him in heaven forever. I am not so certain we want our AIs remaining with us throughout eternity. As with beloved pets, sometimes we need a break. Are we robots for God? Ray thinks such endless replication is possible, BTW. Kurzweil uses the image of Pinocchio throughout to illustrate questions of personhood, with wanting to live, then wanting to live forever.

Every Battlestar Cylon model explained – image from ScreenRant

Persistence of self is a thread here. As noted in the introductory quotes, Kurzweil thinks about whether a person is the same person before and after going through some change. How much change is needed before it crosses some line? Am I the same person I was before I read this book? My skin and bones are older. But they are the same skin and bones. However, I have new thoughts in my head. Does having different thoughts change who I fundamentally am? Where does learning leave off and transition take over? Where does that self go when we die? Can it be reconstructed, if only as a simulacrum? How about experiences? Once experienced, where do those experiences go? These sorts of mental gymnastics are certainly not everyone’s cuppa, but I found this element extremely stimulating.

Kurzweil remains grounded in her personal experience, feelings, and concerns. The book has intellectual and philosophical heft, and concerns itself with far-end technological concerns, but it remains, at heart, a very human story.

As one might expect from an established cartoon artist who has generated more smiles than the Joker’s makeup artist, there are plenty of moments of levity here. Artificial is not a yuck-fest, but a serious story with some comic relief. It is a book that will make you laugh, smile, and feel for the people depicted in its pages. Amy Kurzweil has written a powerful, smart, thought-provoking family tale. There is nothing artificial about that.

I used to wonder if I could wake up into a different self. For all I knew, it could have happened every morning. A new self would have a new set of memories.

Review posted – 01/12/24

Publication date – 10/17/23

I received a hard copy of Artificial: A Love Story from Catapult in return for a fair review.

This review is cross-posted on my site, Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal, FB, Instagram, and Twitter pages

Profile – from Catapult

AMY KURZWEIL is a New Yorker cartoonist and the author of Flying Couch: A Graphic Memoir. She was a 2021 Berlin Prize Fellow with the American Academy in Berlin, a 2019 Shearing Fellow with the Black Mountain Institute, and has received fellowships from MacDowell, Djerassi, and elsewhere.She has been nominated for a Reuben Award and an Ignatz Award for “Technofeelia,” her four part series with The Believer Magazine. Her writing, comics, and cartoons have also been published in The Verge, The New York Times Book Review, Longreads, Literary Hub, WIREDand many other places. Kurzweil has taught widely for over a decade. See her website (amykurzweil.com) to take a class with her.

Interviews

—–NPR – Using AI, cartoonist Amy Kurzweil connects with deceased grandfather in ‘Artificial’ by Chloe Veltman

—–Publishers Weekly – Reincarnation: PW Talks with Amy Kurzweil by Cheryl Klein

—–PC Magazine – How Ray Kurzweil and His Daughter Brought A Relative Back From The Dead By Emily Dreibelbis

——LitHub – Amy Kurzweil on the Open Questions of the Future by Christopher Hermelin

Songs/Music

—–The Jefferson Airplane – White Rabbit– referenced in Chapter 6

Items of Interest from the author

—–Artificial: A Love Story promo vid

—–The New Yorker – excerpt

—–New Yorker – A List of Amy Kurzweil’s pieces for the magazine

Items of Interest

—–Ray Kurzweil on I’ve got a Secret

—–A trailer for Transcendant Man, a documentary about Ray Kurzweil

—–WeBlogTheWorld – Amy interviews Ray in a Fireside Chat at NASA – sound is poor. You will need to ramp up the volume to hear – video – 23:07

—–Wiki on Battlestar Galactica