Inferno is Dan Brown’s 4th Robert Langdon adventure

Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate

or

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here

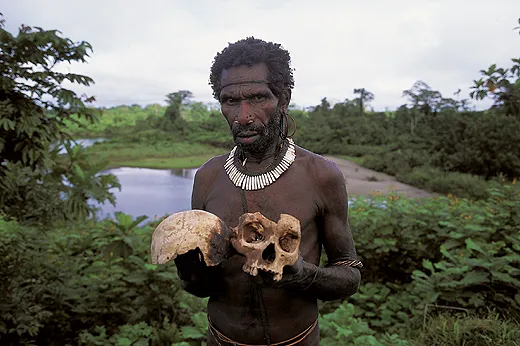

Dante and Virgil approach the entrance to Hell

From the WorldofDante.org

The heat is on. There is, of course, a deadline. A mad scientist of a Dante super-fan, who takes theatrical delight in referring to himself as The Shade, would like to bring about a great renaissance for humanity, a reawakening similar to the one that occurred following the Black Plague. As with that earlier event, The Shade, a Batman villain if ever there was one, would like to cull the world’s population by, oh, say, a third. Malthus lives, and has spawned a group of die-hard Transhumanists who think we and our planet would be a lot better off were there significantly fewer of us using up space, air, water, et al, and hogging the remotes. Robert Langdon, returned to duty after sundry life-threatening adventures in Angels and Demons, The Da Vinci Code, and The Lost Symbol, has been called in to decipher the clues to where and how Mister Zobrist, (we can’t call him The Shade for 463 pages, can we?) conveniently dead in the opening, has set his viral bomb to go off. Or was he? Langdon wakes up in an ER, with a head wound, a distinctly fuzzy recollection of the recent past and thinks he is back in Massachusetts. Brunelleschi didn’t design any buildings in New England. That large dome you see out the window means you are in Florence. Oops. And, by the way, there is a well armed, nicely leather-clad biker person heading down the hall, weapons blazing. Check please. He and Doc McSmokin’, a 208 IQ, blonde, pony-tailed physician, named Sienna Brooks, dash out ahead of the ordnance and the game is afoot. This offers an example of something that is entirely depressing. Had that been an American hospital there is no way he could have gotten out without having to sign insurance forms or promissory notes, guns blazing or not. (Mister Langdon. We need you to sign here, here, here, and initial here, here and here. You, with the gun, take a number and have a seat.)

Woodward and Bernstein, in All the Presidents Men, report on G. Gordon Liddy holding his hand over a flame at a dinner party to impress someone or other. He held it long enough to singe himself, and cause alarm in those present. When he was asked “What’s the trick?” he answered, “The trick is not minding.” Reading a book of Daniel Brown’s is a far cry from holding one’s hand over an open flame. But there are elements to reading his work that are certainly painful. There are benefits to be had, things to be learned, issues to be raised, but there are clichés to be endured, characterizations to be tolerated, dei ex machina to be ignored. I suppose one might think of it as a form of Purgatory. You can certainly enjoy the good while putting up with the bad. The trick is not minding the latter.

One does not descend into reading Dan Brown’s infernal novel expecting literary power. There are certain formulae at work, and if you are not prepared to be led along, keeping the blinders firmly affixed for the duration, you might do better to read something else with the several hours it takes to work your way through the levels in Inferno. (Yes, there are some) We do not expect to find work similar to that of, say, Louise Erdrich, or Ron Rash, and it would be unfair, not to say unkind, to apply to Brown the metrics applied to writers of more serious fiction. But then, what standards should we apply?

There are two general qualities that merit our attention here, and more specific elements within each. Is it entertaining? Is it informative?

Entertaining

Does the story engage out attention? Or do we find ourselves wandering off?

Is it fast-paced?

Do we care about the characters?

Is it fun?

In short, does this make a good beach read?

Informative

Does it teach us something new?

Is the information interesting?

Does it address some larger issue, one of actual significance?

Does it make sense?

ENTERTAINMENT

Does the story engage our attention?

Sure. While not, for me at least, as engaging as The DaVinci Code, I kept turning all 463 pages, eager to find out what there was to be found, info and plot-wise. But I was not exactly panting to get back to the book at every free moment.

Is it fast-paced?

Is the Pope Argentinian? This is what Brown does. Aside from the sort of occasional interruptions that might give the wearer of a pace-maker the sweats, (noted in more detail below) he keeps things moving along. I was reminded of an old (1912) adventure tale, A Princess of Mars, by Edgar Rice Burroughs. That book was also a series. Battle, capture, rescue, escape, repeat, with bits of information about some underlying subject in the book tossed in to grease the narrative wheels. Ditto here.

Speaking of greasing, you will need to have some eye drops handy to avoid chafing from frequent eye-rolling. It seems that every time there is a need to gain access to some large institution, Brown trots out what seems almost a running joke of Robert Langdon having some relationship with the person in charge. I bet if Langdon needed 3am access to the UFO museum in Roswell, we would learn that he had tracked aliens with the museum director and had contributed a live specimen from the Crab Nebula at some time in the not too distant past. The Sulabh International Museum of Toilets? It wasn’t Washington who poohed there, or presented a monograph at the esteemed institution that resulted in such a large inflow of contributions that the institution was flush for a considerable period.

In a related matter, I was reminded of two cinematic clichés in particular. In one, the hero and heroine pause as the world collapses around them to engage in a lengthy soulful smooch. (Pay no attention to that incoming missile. Enjoy.) In the second, a child dashes back to the burning-building or alien-infested-spaceship to retrieve her (choose one – favorite stuffy, kitten, puppy, photo of long dead (but really only missing) mother or father). Brown spares us kittens and overlong liplocks, for the most part, but while Langdon and this volume’s Bond girl are dashing from persistent threats like a Florida race track rabbit, (who are those dogs?) Brown pauses the action every so often, inserts himself and his research into the narrative (Bob, Si, relax. We’ll pick this up again after lunch), and offers up the occasional art history lesson. I’m not saying that these are not informative and sometimes fun (as in the case of a particularly organ-rich Plaza della Signoria)

The Fountain of Neptune from The Museums of Florence

but it does alter the flow in a breathlessly paced novel to…um…take a breather. All right guys, up and at ‘em. Ready, set, flee.

Do we care about the characters?

Truthfully, it is tough not to care about a character that has the face of Tom Hanks ironed onto it, but yeah, I guess, although a lot less than a whole lot of other fictional people. It is fun to see Langdon attempting to recover his memory and figure out who that mysterious woman he keeps seeing in vision-flashes might be. Sienna Galore has a pretty interesting back-story, a large brain, and the usual physical assets required for Brown’s kicked-up Bond-girl roles. So sure, why not. Aside from those two, only a little here and there. Character is not the thing in Dan Brown books.

Is it fun?

As a straight up read, forgetting for the moment one’s analytical inclinations, yes. Brown does revel in puzzles and there are more secrets embedded in Inferno than there are candied items in a fruit cake. And some are quite delicious. (OK, I hereby out myself as a weirdo who likes fruit cake). Unlike one’s experience with fruit cake, however, you will miss out on that weighty feeling of having ingested a brick. Literarily, Inferno is a lot more like chiffon cake than its denser cousin. Also there are enough twists to keep the cap machines at the Nogara Coke bottling factory busy for a long time.

Does it make a good beach read?

Assolutamente

INFORMATION

Does it teach us something new?

Si! We learn of a mysterious transnational entity, that Brown swears is based on a real organization, that smoothes out the curves so that people of questionable motives, but certain resources, can go about their business unimpeded. The head of this group might have been well served with a fluffy white kitty and a pinky ring. Brown offers some nifty tour guides to this and that location in several cities, and a fair bit of history on Dante and his most famous bit of writing. He offers some illuminating details on this or that building, painting and sculpture, including where it might have traveled over the centuries (well, not the buildings, of course) and whether the version we see today is a fully original specimen. He also gives us a very good reason to take a tour of the secret passageways in Old World cities.

The Vasari Corridor from Wiki commons

Is the information interesting?

Leaving aside prophets and their like, before there were mononymous sorts like Liberace, Elvis and Madonna, even earlier than sorts like that English playwright, there was Durante degli Aligheri, known to a certain childhood acquaintance, Beatrice, as that boy who wouldn’t stop staring at her, known to certain priors in Florence as the guy who refused to pay his fine and was thus banned for life, and known to us in the 21st century as Dante.

Dante and His Poem by Michelino from Wikimedia

If you find Dante and his best-known work of interest, and really, you should, this book is a lot of fun. Of course what constitutes interesting is almost always in the eye of the beholder. If your thing is video games, well then not so much. (on the other hand, there actually is a lot here that does remind one of video game action, so I take that back) But if you are fascinated with old world history, art and architecture, Dante, the Black Death, Malthusian concerns, and the potential impact of a large human die-off, then Si, molto.

Does it address some larger issue, one of actual significance?

Sicuramente. Two in fact. One of the major elements in the story is the determination by our psycho-scientist billionaire sort that human population is about to reach a dangerous level, one which is likely to trigger all sorts of catastrophes. There are various ways one can address this concern, but the underlying concern is quite real. Brown does us all a service by bringing it to the attention of millions of readers. Another element here is the notion of “Transhumanism.” Basically this entails humans taking charge of our own evolution and using all the technology available to us to ensure maximization of our physical and intellectual capacities. Whether one sees this as a Satanic plot, yet another opportunity for the haves to have even more, or the beginning of a new human renaissance, the subject is worth checking out.

Does it make sense?

In some ways yes and in some ways no. There is validity to the underlying science. But would the baddie really leave a breadcrumb trail for potential foilers to his big bang?

That said, it can be fun to descend into the bowels of the earth, or the watery substructures of ancient architectural marvels, however many levels down you care to go.

Whether you think that Dan Brown belongs in literary heaven, Hades or somewhere in between, he makes a wonderful Virgil, leading us on an interesting journey, and showing us some things we might not have ever imagined. It may not qualify as a divine book, but Inferno is one hell of a read.

PS – One must note that the end of all three parts of Dante’s Commedia (the Divine was added later) end with the word “stars.” Brown does not disappoint on that score.

And I am sure there is significance to the fact that there are 104 chapters in the book, (plus a prologue and an epilogue, so 106) but I have not been able to suss out exactly what. There are 99 cantos in the Commedia, maybe a couple more with this or that added, but I do not know how one can fluff that up to 106. Yet, I am sure there is an explanation. When (if) I find it I will include it here.

WB2051

========================================EXTRA STUFF

Apparently the city of Manila took umbrage at a negative characterization in the book

An interesting discussion of Dante’s work

Wiki article on transhumanism

Washington Post review

Janet Maslin’s NY Times review, which includes a wonderful observation re the book’s publication date

WSJ piece on how Dan Brown kept the wraps on his story lest copycats scoop him

For some nice images and info on the Vasari Corridor

If you get the urge, you can read Dante’s masterpiece thanks to the Gutenberg project

If you believe that Dan Brown should be relegated to one of the lower levels of hell, you might enjoy this piece in The Daily Beast, by Noah Charney, who clearly enjoys pointing out all the things Brown got wrong

GR friend Connie reminds us that there is a wonderful piece by Rodin, The Gates of Hell, that is worth a look.

Here is a nice Q&A piece with Brown from the June 20, 2013, NY Times, part of their By the Book series

Some interesting images and notions on Dante’s hell, on a web post called The Topography of Hell

I guarantee that when you reach the end of this novel the sound you hear will be coming from your own mouth, “Awwwwwwwwww.”

I guarantee that when you reach the end of this novel the sound you hear will be coming from your own mouth, “Awwwwwwwwww.”

Winter is coming.

Winter is coming.