Men, can’t live with ‘em, can’t turn ‘em all into swine.

What do you mean turn them into swine? From her earliest application of her new found transformative skills it is suggested that what Circe turns her unfortunate guests into has more to do with their innermost nature than Circe’s selection of a target form. (The strength of those flowers lay in their sap, which could transform any creature to its truest self.) Clearly her sty residents had an oinky predisposition. And I am sure that there are many who had started the transformation long before landing on her island.

Whaddya call the large sty Circe filled with erstwhile men? A good start.

Ok. You had to know this would be part of the deal for this review. So, now that I have gotten it out of my system, (it is out, right?) we can proceed.

When I was born, the name for what I was did not exist.

It was a word that Barbara Bush might have had in mind when she described Geraldine Ferraro, her husband’s opponent for the Vice Presidency, in 1984. “”I can’t say it, but it rhymes with ‘rich,'” she said, later insisting that the word in question did not begin with a “b,” but a “w.” Sure, whatever. But in this case, I suppose both might apply. Circe is indeed the first witch in western literature. And many a sailing crew might have had unkind things to say about her.

Madeline Miller – image from The Times

Our primary introduction to Circe (which we pronounce as Sir-Sea, and even Miller goes along with this, so people don’t throw things at her. But for how it might be pronounced in Greek, you know, the proper way, you might check out this link. Put that down, there will be no throwing of things in this review!) was that wondrous classic of Western literature, The Odyssey. Given how many times this and its companion volume, The Iliad, have been reworked through the ages, it is no surprise that there have been many variations on the stories they told. Circe’s story has seen its share of re-imaginings as well. But Miller tries to stick fairly close to the Homeric version. Be warned, though, some license was taken, and other sources inspired the work as well. But it is from Homer that we get the primary association we have with her name, the magical transmutation of men into pigs.

George Romney’s 1782 portrait of Emma Hamilton as Circe – image from wikipedia

We follow the life of our Ur-witch from birth to whatever. She did not start out with much by way of godly powers. Her mother, Perse, daughter of the sea-god Oceanos, was a nymph, and her father was Helios, the sun god. Despite the lofty position of Pop’s place in things, Circe was just a nymph, on the low end of the godly powers scale. This did not help in the family to which she had been born. Not one of her parents’ favorites, she was blessed with neither power nor beauty, had a very ungod-like human-level voice, and her sibs were not exactly the nicest. Kinda tough to keep up when daddy is the actual bloody sun.

Years pass, and one day she comes across a mortal fisherman. He seems pretty nice, someone she can talk to. She’d like to take it to the next stage, so she lays low, listens in on family gatherings, and picks up intel on substances that might be used to effect powerful and advantageous changes. She asks her grandmother, Tethys, (very Lannisterish wife AND SISTER to Oceanos) to transform him into a god for her, but Granny throws her out, alarmed when her granddaughter mentions this pharmakos stuff she had been looking into. Left to her own devices she tries this out on her bf, making him into his truest self. It does not end the way she’d hoped. (Pearls before you-know-what.) Not the last bad experience she would have with a man.

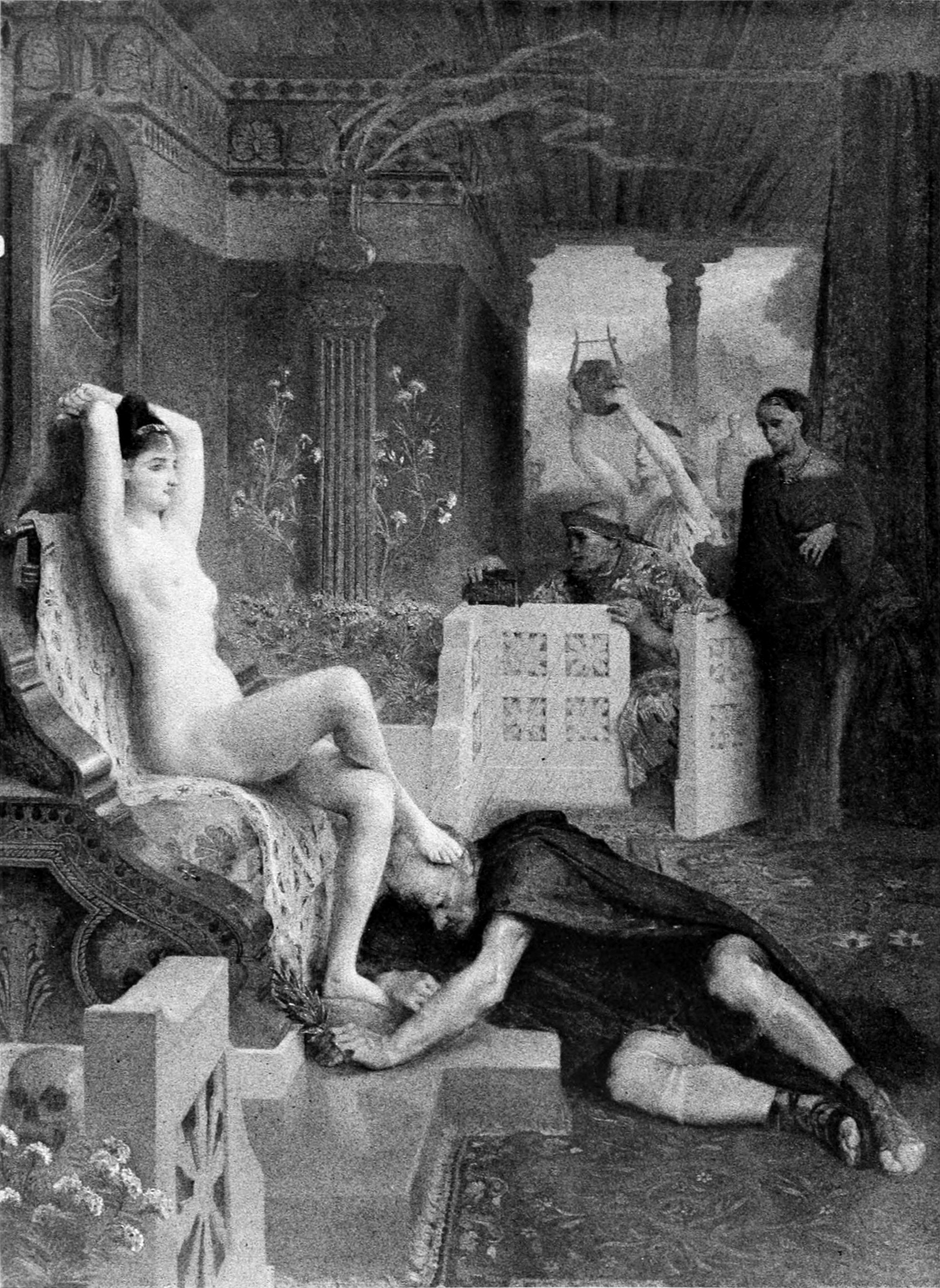

Levy’s 1889 Circe – image from wikipedia (is that a foot soldier?)

Her relationships with men are actually not all bad. Daddy is singularly unfeeling, and can be pretty dim for such a bright bulb, and her brothers are far less than wonderful, but there is some good in her sibling connections as well. She has a warm interaction with a titan, Prometheus, which is a net positive. Later, she has an interesting relationship with Hermes, who is not to be trusted, but who offers some helpful guidance. And then there are the mortals, Daedalus (the master artist, the Michelangelo, the Leonardo da Vinci of his era), Jason, of Argonaut fame, Odysseus, who you may have heard of, and more. There were dark encounters as well, and thus the whole turning-men-into-pigs thing.

Brewer’s 1892 Circe and Her Swine – image from Wikipedia

Miller has had a passion for the classics since she was eight, when her mother read her the Iliad and began taking her to Egyptian and Greek exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. It made her a nerdy classmate but was a boon when she got to college and was able to find peers who shared her love of the ancient tales. It was this passion that led her to write her first novel, The Song of Achilles, a reimagining of Achilles relationship with his lover, Patroclus, a delight of a book, a Times bestseller, and winner of the Orange prize. It took her ten years to write her first novel, about seven for this one and the gestation period for number three remains to be seen. She is weighing whether to base it on Shakespeare’s The Tempest or Virgil’s Aeneid. If past is portent, it will be the latter, and should be ready by about 2025.

Ulysses and Circe, Angelica Kauffmann, 1786. – image from Miller’s site

The central, driving force in the story is Circe becoming her fullest possible self. (I suppose one might say she made a silk purse from a sow’s ear. I wouldn’t, but some might.)

This is the story of a woman finding her power and, as part of that, finding her voice. She starts out really unable to say what she thinks and by the end of the book, she’s able to live life on her terms and say what she thinks and what she feels. – from the Bookriot interview

Most gods are awful sorts, vain, selfish, greedy, careless of the harm they do to others. Circe actually has better inclinations. For instance, when Prometheus is being tortured by the titans for the crime of giving fire to humans, Circe alone is kind to him, bringing him nectar, and talking with him when no one else offers him anything but anger and scorn. She is curious about mortals, and asks him about them, going so far as to cut herself to experience a bit of humanity.

Carracci’s c. 1590 Ulysses and Circe in the Farnese Palace – image from Wikipedia

Livestock comes in for some attention outside the sty. Turns out Circe’s father has a thing for a well-turned fetlock, so maybe she comes by her affinity for animals of all sorts, albeit in a very different way, quite naturally. Her island is rich with diverse fauna, including some close companions most of us would flee. An early version of Doctor Doolittle?

Scholars have debated whether Circe’s pet lions are supposed to be transformed men, or merely tamed beasts. In my novel, I chose to make them actual animals, because I wanted to honor Circe’s connection to Eastern and Anatolian goddesses like Cybele. Such goddesses also had power over fierce animals, and are known by the title Potnia Theron, Mistress of the Beasts.

Not be confused with The Beastmaster

Circe and Odysseus. Allessandro Allori, 1560 – image from Miller’s site

While she has her darker side (she does change her nymph love-rival Scylla into a beast of epic proportions, which gets her sent to her room, or in this case, island, and there is that pig thing again) she is also a welcoming hostess on her isle of exile, Aiaia. (Which sounds to me like the palindromic beginning of a lament, Aiaiaiaiaiaiaia, which might feel a bit more familiar with a minor transformation, to oy-oy-oy-oy-oy-oy-oy-oy). I mean, she runs a pretty nifty BnB, with free-roaming wild animals, of both the barnyard and terrifying sort, a steady flow of wayward nymphs sent there by desperate parents in hopes that Circe might transform them into less troublesome progeny, a table with a seemingly bottomless supply of food and drink. And she is more than willing to offer special services to world-class mortals, among others. I mean, after that little misunderstanding with Odysseus about his men, (Pigs? What pigs? What could you possibly mean? Oh, you mean those pigs. Oopsy. How careless of me.) she not only invites everyone to stay for a prolonged vacay, but shacks up with the peripatetic one, offers him instructions on reaching the underworld, suggests ways to get past Scylla and Charybdis, and probably packs bag lunches for him and his crew. She is not all bad.

Barker’s 1889 Circe – image from Wikipedia

Circe struggles with the mortals-vs-immortals tension. Her mortal voice makes her less frightening to the short-lived ones, allowing her to establish actual relationships with them that a more boombox-voice-level deity might not be able to manage. Of course, it is still quite limiting that even the youngest of her mortal love interests would wither and die while she remained the same age pretty much forever. Knowing that you will see any man you love die is a definite limiting factor. Yet, she manages. She certainly recognizes what a psycho crew the immortals are, even her immediate family, and respects that mortals who gain fame do so by the sweat of their brow or extreme cunning, (even if it is to dark purpose) not their questionable godly DNA. Reinforcing this is her front row seat to the real-housewives tension between the erstwhile global rulers, the Titans, and the relatively new champions of everything there is, the Olympians. I mean, perpetual torture, thunderbolts, ongoing seditious plots, the nurturing of monsters, wholesale slaughter of mortals? She knows a thing or two, because she’s seen a thing or two.

My thoughts about [Circe as caregiver] really start with the gods, who in Greek myth are horrendous creatures. Selfish, totally invested only in their own desires, and unable to really care for anyone but themselves. Circe has this impulse from the beginning to care for other people. She has this initial encounter with Prometheus where she comes across another god who seems to understand that and also who triggers that impulse in her. I wanted to write about what it’s like when you to want to try to be a good person, but you have absolutely no models for that. How do you construct a moral view coming from a completely immoral family? – from Bookriot interview

Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus – by John William Waterhouse – 1891 – image from Wikimedia

Of course, there is a pretty straight line between the sort of MCP hogwash Circe had to endure in the wayback and recent events that have been getting so much attention of late

“I wasn’t trying to write Circe’s story in a modern way… I was just trying to be true to her experience in the ancient world.”

“It was a very eerie experience. I would put the book away and check the news. The top story was literally the same issue I had just been writing about — sexual assault, abuse, men refusing to allow women to have any power … I was drawn to the mystery of her character — why is she turning men into pigs?” – from The Times interview

There are plenty of classical connections peppered throughout Circe’s tale. Jason and Medea (niece) pop by for a spell. She is summoned to assist in the birthing of the minotaur (nephew) to her seriously nasty sister. She is part of Scylla’s origin story, interacts with Prometheus (cousin), gives shit to Athena, even heads into the briny deep to take a meeting with a huge sea creature (no, not the Kraaken). Hangs with Penelope (her bf’s wife) and Telemachus (bf’s son), and spends a lot of time with Hermes. She definitely had a life, many even, particularly for someone who was ostracized to live on an island.

For Circe, I would say the Odyssey was my primary touch-stone in the sense that that’s where I started building the character. I take character clues directly from Homer’s text, both large and small. I mentioned her mortal-like voice. The lions. The pigs. And then when I get to the Odysseus episode in the book, I follow Homer obviously very closely… – from the BookRiot interview

“Circea”, #38 in Boccaccio’s c. 1365 De Claris Mulieribus, a catalogue of famous women, from a 1474 edition – image from wikipedia

In terms of sources, I used texts from all over the ancient world and a few from the more modern world as well. For Circe herself, I drew inspiration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica, Vergil’s Aeneid, the lost epic Telegony (which survives only in summary) and myths of the Anatolian goddess Cybele. For other characters, I was inspired by the Iliad, of course, the tragedies (specifically the Oresteia, Medea and Philoctetes), Vergil’s Aeneid again, Tennyson’s Ulysses and Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida. Alert readers may note a few small pieces of Shakespeare’s Ulysses in my Odysseus! – from Refinery29 interview

Circe – by Lorenzo Garbieri – image From Maicar Greek Mythology Link

Madeline Miller’s Circe is not a lovelorn, lonely heart desperate for connection in her isolation, but a multi-faceted character (not actually a human being, though), with inner seams of the dark and light sort, with family issues that might seem familiar in feel, if not in external content, with sins on her soul, but a desire to do good, and with a curiosity about the world. She may not have been the brightest light in the house of Helios, but she glowed with an inner strength, a capacity for mercy, an appreciation for genius, beauty and talent, and a fondness for pork. This is the epic story of a life lived to the fullest. Circe is an explorer, a lover, a destroyer, and can be a very angry goddess. This transformative figure is our doorway to a very accessible look at the Greek tales which lie at the root of so much of our culture. If you have a decent grounding in western mythology this will offer a delightful refresher. If you do not, it can offer a delightful introduction, and will no doubt spark a desire to root about for more. Madeline Miller may not have a wand with special powers, or transmogrifying potions at her command, but she demonstrates here a power to transform mere readers into fans. Circe is a fabulous read! You will go hog wild for it. Can you pass the hot dogs? That’s All Folks

The Sorceress Circe, oil painting by Dosso Dossi, c. 1530; in the Borghese Gallery, RomeSCALA/Art Resource, New York – image from Britannica

Review first posted – 4/27/2018

Publication date – 4/10/2018

December 2018 – Circe wins the 2018 Goodreads Choice Award for favorite Fantasy novel of the year

This review has been cross-posted on Goodreads. Stop by and say Hi!

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal, Twitter and FB pages

Interviews

—– BookPage – April 10, 2018 – Madeline Miller – The season of the witch – by Trisha Ping

—–Bookriot – April 19, 2018 – Writing of Gods and Mortals: A Madeline Miller Interview – by Nikki Vanry

—–The Times – April 5, 2018 – The Magazine Interview: Madeline Miller, author of this summer’s must-read novel, Circe, on seeing history through women’s eyes – by Helena de Bertodano

NY Times – April 6, 2018 – A lovely profile from the NY Times – Circe, a Vilified Witch From Classical Mythology, Gets Her Own Epic – by Alexandra Alter

My review of The Song of Achilles

The Odyssey on Gutenberg

A very nifty, brief, and entertaining summary of The Odyssey can be found on Schmoop.com.

A fitting piece of music from Studio Killers

Reading Group Guide from Catapult

==========================================STUFFING

A wonderful piece from Allan Ishac at Medium, on the Russia investigation. – Mueller Tells Staff: “This Swine Is Mine”

President Trump is ready for slaughter, according to people inside Robert Mueller’s office. (Credit: wemeantwell.com and imgur.com) – from above article. (turned out Mueller was hamstrung in what he could investigate, among other issues)

There are so many elements to Some Luck, long-listed for the 2014 National Book Award, that wherever your interests may lie, there is much here from which to choose. Take your pick—a Pulitzer-winning author going for a triple in the late innings, finishing up her goal of writing novels in all forms. Take your pick—a look at 34 years of a planned hundred year scan of the USA through the eyes of a Midwest family, winning, engaging characters, seen from birth to whatever, good, bad and pffft, where’d that one go? Take your pick—a look at the changes in farming, over the decades, the impact of events like the Depression and massive drought on people you care about. Take your pick—the impact of the end of World War I on the breadbasket, a sniper’s eye view of World War II, the chilly beginning of the Cold War. Take your pick– the searing summer heat that killed many, the biting snow-bound winter that stole the heat from every extremity. Take your pick– an infant’s eye view of learning to speak, a teenager’s look at awakening sexuality, an older man looking back on his life. Take your pick—the newness and revolution of cars, tractors, hybrid plants, new fertilizer, the tales brought from the old country, often told in foreign tongues. Take your pick—a bad boy with talent, brains and looks, a steadfast young man taking the old ways of farming and mixing them with the new to make a life and a future, a smart young woman heading to the big city and getting involved with very un-farm-like political interests. Take your pick—shopping for a religion while looking for answers to the sorrows of existence, shopping for political help when no financial seems forthcoming from the nation. Take your pick—love is found, lost, found again, couples struggle through ups and downs, the charring of fate and time, the questions that arise, the doubts, the certainties. Take your pick.

There are so many elements to Some Luck, long-listed for the 2014 National Book Award, that wherever your interests may lie, there is much here from which to choose. Take your pick—a Pulitzer-winning author going for a triple in the late innings, finishing up her goal of writing novels in all forms. Take your pick—a look at 34 years of a planned hundred year scan of the USA through the eyes of a Midwest family, winning, engaging characters, seen from birth to whatever, good, bad and pffft, where’d that one go? Take your pick—a look at the changes in farming, over the decades, the impact of events like the Depression and massive drought on people you care about. Take your pick—the impact of the end of World War I on the breadbasket, a sniper’s eye view of World War II, the chilly beginning of the Cold War. Take your pick– the searing summer heat that killed many, the biting snow-bound winter that stole the heat from every extremity. Take your pick– an infant’s eye view of learning to speak, a teenager’s look at awakening sexuality, an older man looking back on his life. Take your pick—the newness and revolution of cars, tractors, hybrid plants, new fertilizer, the tales brought from the old country, often told in foreign tongues. Take your pick—a bad boy with talent, brains and looks, a steadfast young man taking the old ways of farming and mixing them with the new to make a life and a future, a smart young woman heading to the big city and getting involved with very un-farm-like political interests. Take your pick—shopping for a religion while looking for answers to the sorrows of existence, shopping for political help when no financial seems forthcoming from the nation. Take your pick—love is found, lost, found again, couples struggle through ups and downs, the charring of fate and time, the questions that arise, the doubts, the certainties. Take your pick.