…the sensors jammed into a mako’s head resemble the cockpit of an F-35 fighter jet. [presumably without the design flaws and cost overruns] The mako’s sensors are equal in sophistication to the fighter jet’s advanced systems except they are bundled in nerves, flesh, and blood.

Not comforting.

It was the shark tournament that spurred him to action. William McKeever has had a lifelong interest in sharks, ever since his father took him fishing in Nantucket Sound as a kid. An encounter with a caught (and released) dogfish led to long curiosity-driven hours at the library, hunting down, then devouring all he could find on sharks. A few years ago, a lifetime later, on a weekend in Montauk, he got to see appalling scene after appalling scene, large numbers of sharks on display, most thrown away post photo, a Breughelesque scene of mindless genocidal mayhem, otherwise known as the Montauk Shark Tournament. A bit more research revealed that, despite the bad rap sharks have gotten from our popular media, (I mean you, Spielberg) most shark “attacks” are the equivalent of a dog bite. It really is the sharks who are probably wondering if it’s safe to go back into the water.

While sharks kill an average of four humans a year, humans kill 100 million sharks each year. That is not a typo. Humans kill 100 million sharks each year.

William McKeever – image from McKeever’s site

Many of us engage in small ways to try to help when we see outrages in the world. Whether that means trying to help elect public officials who share our concerns, contributing to non-profits engaged in doing battle in our particular areas of concern, maybe volunteering to help out in some way. McKeever was a Wall-Street managing director at Paine Webber, UBS, and Merrill Lynch, and an analyst for Institutional Investor magazine, sharing his expertise on NBC, CNBC, the Wall Street Journal. But it turned out he had bigger fish to fry, and his financial success on Wall Street allowed him the means to pursue his passion. Bringing to light the damage that recreational fishing, particularly scenes of carnage like the one he had seen at Montauk, and the even greater mass annihilation of the world’s shark population by commercial fishing, became his mission. In 2018, he founded a conservancy tasked with helping protect sharks and other fish that man is wiping out, by showing sharks in a new light, as the magnificent creatures they are, survivors extraordinaire, who were here before the dinosaurs, and will probably still be here after people are gone, if we don’t wipe them out first.

Hammerhead Shark – image from McKeever’s site

In order to put together educational materials. You need to learn what there is to learn. Although McKeever’s interest had been of long-standing, and although he knew a hell of a lot, having produced two documentary films about sharks, McKeever visited major oceanographic facilities across the planet, interviewed leading scientists and conservationists, and distilled what he learned down to a very readable and informative 295 pages. In addition to producing this book, he and his team are working on a documentary film. It should be available in 2020. (hmmm, 2023 and we are still waiting, so not a sure thing.)

Tiger Sharks – image from McKeever’s site

His investigative sojourn took two years, and was truly global, from Montauk, and Cape Cod, to the Florida coast and Keys, the Dry Tortugas, and Hawaii. He traveled to Taiwan, Cambodia, Australia, South Africa and the Bahamas. And I am sure I missed a few. He also interviewed experts, without literally diving in, in many other locations.

The Dry Tortugas – Bush Key – from our vault

While occasionally these field trips were duds, not sighting anything more than a descending dorsal fin in Shark Alley, SHARK bloody ALLEY in South Africa, (although to be fair, not seeing sharks in Shark Alley does speak to the impact humans have had on shark population, so maybe not a dud after all), or noting his arrival in a place just to tick the box and then off to some other place. But mostly the first-person accounts of his meetings with a diverse set of experts, and his observations, both land-based and in the water, are illuminating, sometimes very surprising, and sometimes somewhat grim.

Shark Alley in rush hour – image from National Geographic

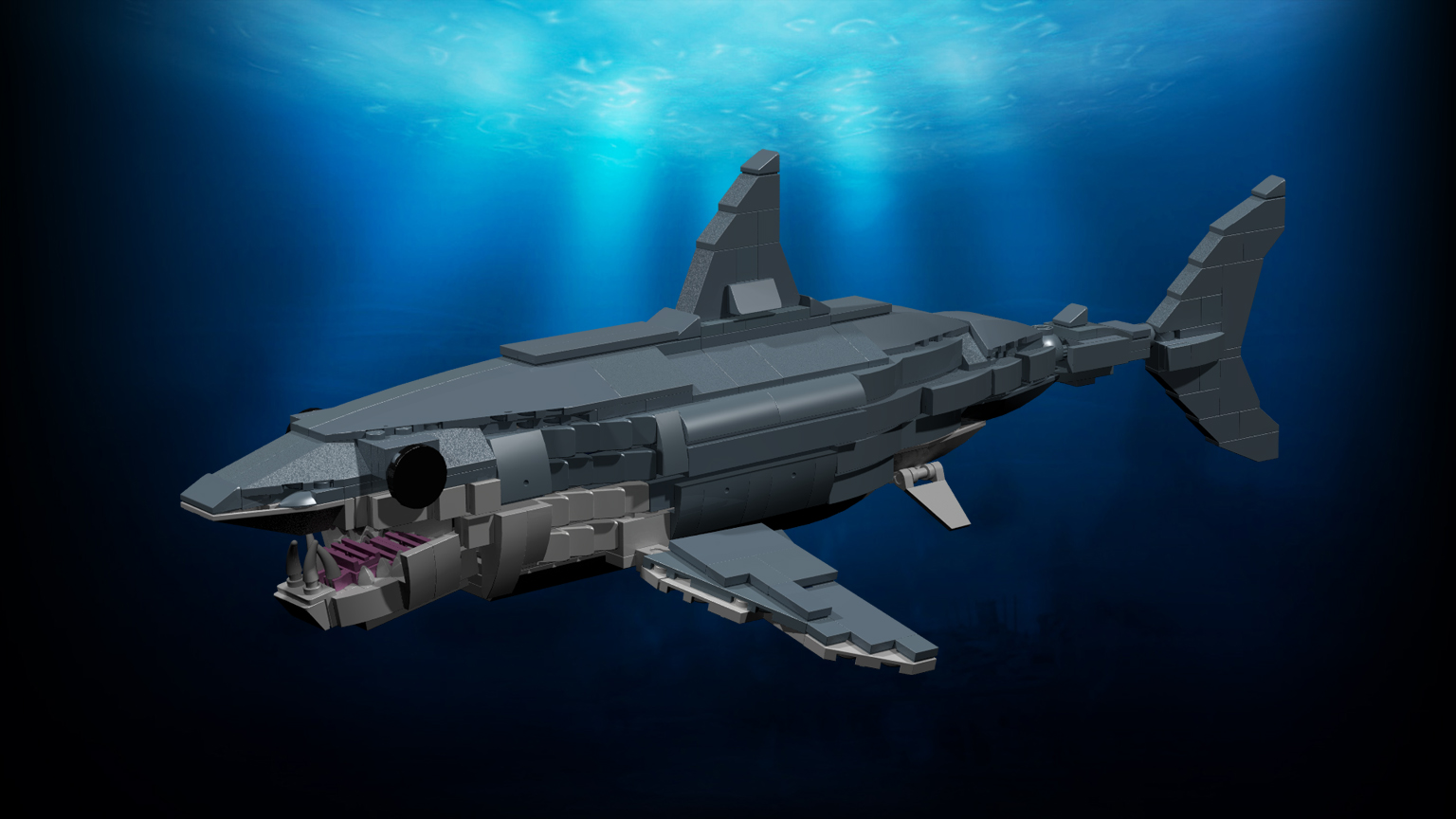

McKeever concentrates on four sharks in particular, the Mako, Tiger, Hammerhead and Great White, offering fascinating information about each.

Numerous popular articles have described the brain of a white shark as being the size of a walnut, a misleading and inaccurate comparison. The brain of an adult white shark is shaped like a “Y,” and from the scent-detecting bulbs to the brain stem, a shark’s brain can measure up to approximately 2 feet in length…relative to the body weight of birds and marsupials…the great white’s brain is massive.

Makos and Great Whites hunt using their blazing speed, then close the deal with insanely powerful jaws, nicely lined with many large, very sharp teeth; Tiger sharks are also deadly fast, but they prefer to swim slowly and ambush prey with a sudden burst of speed.

Tiger sharks like to sneak up on divers, disappearing and reappearing like a magician’s trick, which unnerves many. Can’t imagine why.

Mary Lee – a great white with over 75,000 FB followers- image from her site

Sharks serve a very useful function in marine ecology. An impressive list of items found in very omnivorous Tiger shark stomachs, boat cushions, tin cans, license plates, tires, the head of a crocodile, for example, reinforces the notion that the shark is a high-tech machine assigned the modest job of ocean cleanup.

When tigers remove garbage—weak and sick fish—they remove from the ocean bacteria and viruses that can harm reefs and seagrass. However, the tiger’s work extends beyond mere custodial work: as apex predators, tiger sharks play an important role in maintaining the balance of fish species across the ecosystem. Moreover, the research shows that areas with more apex predators have greater biodiversity and higher densities of individuals than do areas with fewer apex predators.

Sorry, no Land Sharks.

Land shark – image from from SNL Fandom

Sharks face considerable dangers beyond the risk of chowing down on diverse awful flavors of tire and tags that are not to their liking. You will share McKeever’s outrage when you read his description of the Montauk Tournament. There are gruesome descriptions of the vile, cruel behavior engaged in by people on commercial, and some sport fishing vessels. It makes one ashamed to be a human. You will shudder when you read of the practice of finning, done to satisfy the booming Asian demand for shark fin soup. Sharks face huge perils from sports fishermen, but the greatest danger is from long-lining. Ships drop fishing lines that are sometimes tens of miles long, with a baited hook every few feet. The catch is massive, but only part of what is caught is what the fishermen want. The rest, called bycatch, is thrown overboard, usually dead, sometimes not. It is the equivalent of clearcutting forests or mountaintop-removal mining. Kill them all and toss what you don’t want. Thus the stark disparity in shark-deaths-by-human versus human-deaths-by-shark. McKeever looks at what is likely the impact of climate change on some places where one might expect sharks in abundance but in which they have become scarce.

Denticles on a hammerhead – image from hammerheadsharks.weebly.com

There are many details about sharks that may force the word “wow” or “cool” from your lips. Like denticles. Rub a shark’s skin (a small, friendly shark) one way, and it is smooth. Reverse direction and it will feel like sand paper, or worse. Millions of years ago, sharks traded scales in for dermal denticles. These are small scale-like growths that function both as a sort of chain-mail protection and as an aid to swimming speed, as they reduce friction. Ok, you may have known about those, but what about a cephalofoil? Yeah, go ahead, look it up.

The Rainbow Warrior – image from Greenpeace

McKeever spends some time on The Rainbow Warrior, Greenpeace’s well-known vessel, learning a great deal about the challenges marine creatures face from unregulated international fishing. The chapter on human trafficking in the fishing industry is must-read material. You will be shocked at what he learned. It is clear that owners of fishing vessels that use and mistreat slave labor have no more regard for human life than they do for the sharks they slaughter by the millions. It was news to me that many of these ships remain at sea for years at a time, offering not even the possibility of escape for desperate captives. I had no idea.

While the book is not suffused with the stuff, McKeever shows a delightful sense of humor from time to time. This is most welcome in a tale that can be quite upsetting at times. His writing is clear, direct, and mostly free of poetic, rapturous description, which is just fine. He tells what he has learned and believes is important for us to know. His personal experiences with close encounters of the shark kind are engaging and relatable.

Shark brain -image from wikimedia

You will learn a lot from Emperors of the Deep. Some information may be a bit familiar, but I found that there was a lot in here that was news. I expect most of us have some general knowledge of sharks, and the image in our heads is probably the one created by Steven Spielberg in 1975. One of the best things you will get from this book is at least some appreciation for the range of sharks that share our planet, and what differentiates them from each other, but much more importantly an appreciation for how critical they are to the ecosystem, how much of a threat to people they aren’t, and how quickly we are wiping them out. There is a shark that swim sideways. Whoda thunk? You will gain a new appreciation for the significance of sea grass as a key player in the sustenance of marine ecosystems.

Seagrass – image from Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Gripes – The book could really use an index. There is a center section with color photographs. These are fine. I would have preferred graphics, whether drawings or photos, that illustrated the notions he was describing, particularly as regards shark anatomy. There are times when the author seems to lose his focus. For instance, his visit to Brisbane and a bit of attempted kayaking in a rough sea may have been a fun memory for him, but had not much to do with the mission of the book, as he dashes off 340 miles to catch a ferry to the Coral Sea, where the subject at hand is re-engaged. Descriptions of a shark brain, or denticles, differences in the eyes of diverse species, and sundry more items would have been greatly enhanced by the presence of right-there images. More curiosity than a gripe, I wondered about what McKeever had been up to between the time he left Merrill Lynch and when took up conservation. Finally, the book could have used a list of organizations mentioned in the book, with contact information.

Lego Mako Shark – image from ideas.lego.com

McKeever, in attempting to rebrand sharks from man-eating monsters to vanishing species, makes the case that we need apex predators to thrive, that they are crucial to maintaining biodiversity, and healthy marine ecosystems. He fills us in on the value of healthy shark populations to the tourism industry. He fills us in on just how amazing and diverse these creatures are, and reports on fishing practices that are certain to push global shark populations to the brink of extinction, if international law, regulation, and enforcement are not directed at the problem. He also offers some hopeful examples of positive programs that are making or seek to make a difference.

Cage diving is one way sharks contribute to ecotourism – image from Scubaverse.com

If they were able to articulate the notion, sharks would surely be thinking that, with the attacks they are constantly suffering, they’re gonna need a bigger planet.

When Americans eat canned tuna, they do not realize the destruction of the ocean that their meal represents. Imagine if producing a single hamburger required butchers to kill not only the cow but all the other barnyard animals too.

Review first posted – August 3, 2019

Publication dates

—–June 25, 2019 – Hardcover

—–May 26, 2020 – Trade paperback

=======================================EXTRA STUFF

Links to the author’s personal, and FB pages

McKeever has a Twitter page, last updated in April, 2020, and his LinkedIn page is long out of date.

McKeever also has a documentary in the works on plastics in the oceans -looks like he is still looking for a producer for that.

Interviews

—–NY Post – Why sharks aren’t as bad as ‘Jaws’ makes them out to be – by Eric Spitznagel

—–Feather Sound News – In an interview with CMRubinWorld for Earth Day, April 22, 2019, author, conservationist and filmmaker William Mckeever corrects common misconceptions about the world’s most feared and misunderstood predators. – (not big on snappy headlines, are they)

—–The Cape Cod Chronicle – Researcher Uses Book, Film In Quest To Protect Sharks by Debra Lawless

Items of Interest

—–Excerpt – Fox News William McKeever: Sharks aren’t quite the threat that ‘Jaws’ portrayed

—–Mary Lee’s Facebook page – Mary Lee is noted in the book as a tagged shark that had developed a global following, as her peregrinations were tracked

—–Mary Lee’s Twitter page

—–Adventure Sports Network – Is the Famed Great White Shark, Mary Lee, Gone Forever? – by Jon Coen

—–OCEARCH

—–Discovery schedule for Shark Week, the latest season. There will be a 2024 season, but details are yet to be released (as of August 2023)

—–July 2020 – National Geographic – Sizing Up Sharks, the Lords of the Sea – a fun graphic look at shark size vis a vis us

Videos

—–Baby Shark

—–Lesley Rochat – Rethink the Shark – CHECK THIS OUT!!!

—–Book Trailer